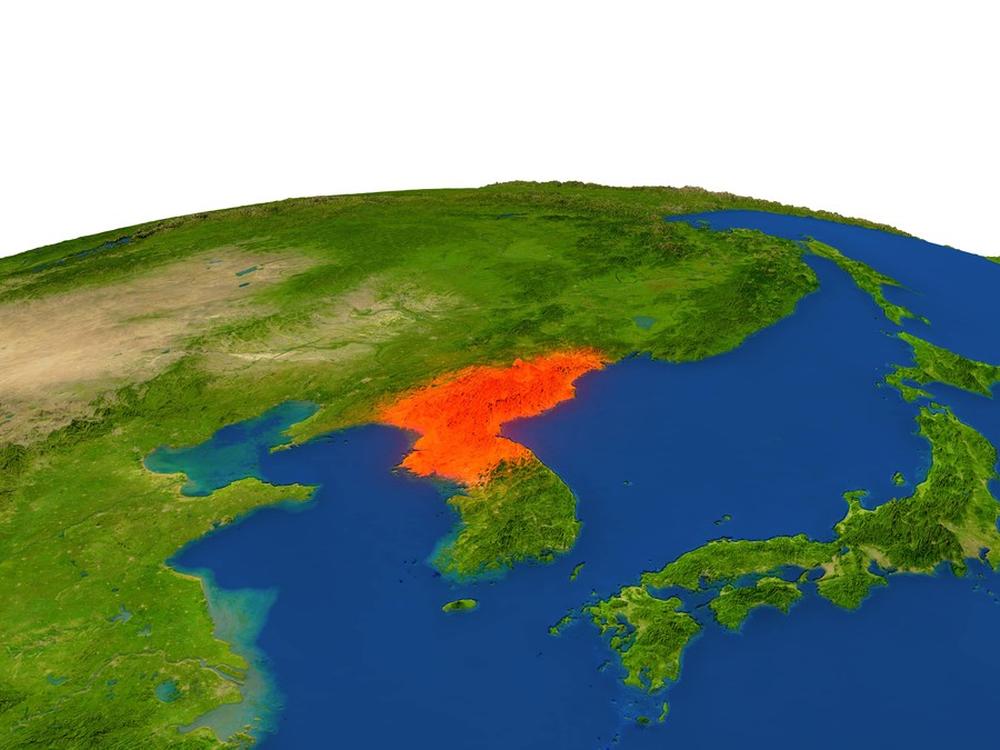

- #North Korea

- #Sanctions & Human Rights

- #South Korea

► The parlous state of human rights in North Korea has been a concern to the world’s established democracies for decades, across three iterations of the hereditary Kim regime.

►This is a story with two silver linings: first, the marketization of the North Korean economy; and second, the fostering of widespread international awareness of the normatively outrageous nature of the country’s repression of its people.

There is nothing new under the sun, or under the son. The parlous state of human rights in North Korea has been a concern to the world’s established democracies for decades, across three iterations of the hereditary Kim regime. Venezuelan poet and committed communist Ali Lameda was sentenced to 20 years in a North Korean prison camp as far back as 1967. That was the year the Beatles played Shea Stadium. Ostensibly imprisoned for espionage and “sabotaging” the North Korean revolution, whatever that meant, Lameda was adopted as a prisoner of conscience by none other than Amnesty International in 1974, leading to his release later the same year.

But while the Lameda case was cut from a cloth that has since become very recognizable, it is also from a bygone age. North Korea in 1967 was an abusive, authoritarian, and disreputable place in many ways, but it was incomparable to the human rights catastrophe that came later. The second Kim regime’s political and economic choices helped usher in the worst of the famine that killed a million people or more between 1995 and 1998. Though initially bringing with him hopes for change and a measure of economic reform, the third Kim regime, that of Kim Jong Un, has regressed into a depressingly familiar pattern.

This is a story with two silver linings: first, the marketization of the North Korean economy; and second, the fostering of widespread international awareness of the normatively outrageous nature of the country’s repression of its people. This second phenomenon led in due time to an activist movement of considerable scale and voice. It began with the defection of former Workers’ Party secretary Hwang Jang Yop in 1997 and creation of the world’s first dedicated North Korean human rights NGO, NK Net, in 1999, then peaked in March 2013 with the creation of a UN Commission of Inquiry (COI) into the full spectrum of North Korean human rights abuses. The pace has abated somewhat since then, but the work continues.

One might reasonably presume that South Korea, a democracy since the late 1980s and a fully consolidated one for some considerable time now, as well as a dynamic and rapidly advancing economy and society, would have exercised leadership in this process. With its lingering attachment to ethnic nationalism and a constitutional claim to be the only legitimate government of the whole Korean peninsula, Seoul had ample reason to do so.

And on occasion, South Korean leaders did indeed marshal resources to lead the fight for North Korean human rights. In 2015, for example, in accordance with a recommendation of the ground-breaking COI report, a UN office was established to further the work of the commission and “help lay the basis for future accountability,” in the words of the then-UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. That office was established in Seoul.

But for the most part, South Korea has not been able to maintain a consistent policy in this area. That Seoul has been unable to cement its leading position through multiple electoral cycles reflects a simple fact: “North Korea” is a domestic political variable in South Korea, and a contested one. The “North Korea problem” is a salient policy issue for voters, especially older ones. The decisions of South Korean political actors to invoke North Korean human rights or not to do so are, in the end, domestic political choices, whether it be the decision of the administration of President Moon Jae-in not to co-sponsor resolutions on North Korean human rights in the UN General Assembly and Human Rights Council after 2019, or the decision of two immediately preceding conservative administrations to do exactly that.

Inevitably, then, the July 2022 decision of the new administration of President Yoon Suk Yeol to appoint an envoy for North Korean human rights was also domestically political in nature. One can be in no doubt as to the motivations of the envoy, Prof. Lee Shin-hwa. But it has been clear from the outset that the Yoon administration does not prioritize North Korea. Indeed, Yoon has not hidden his preferences, famously avoiding any mention of North Korea in his debut UN General Assembly speech on 21 September.

At home, too, the Yoon administration set out its stall very clearly, not only in the spirit of putting distance between itself and the previous government of President Moon, which many felt focused rather too much on inter-Korean relations, but also based upon a rational calculation of where South Korea’s true interests lay. Alliance with the United States is central, relations with the global community of democracies – including Japan – follow, the challenge posed by China is to be managed as best it can be in light of Korean economic dependency, and Seoul has a fine line to walk over the Ukraine conflict. There is no place for North Korea.

This dichotomy explains why, despite its positive rhetorical stance on human rights, South Korea will need to act fast to prove conclusively that its newfound (again) commitment to the matter has any serious ambition behind it. Certainly, there are some positive signs. In addition to the appointment of Prof. Lee, Seoul voted in the UN Human Rights Council in favour of opening a debate on human rights violations in Xinjiang, at the obvious cost of upsetting Beijing. The South has been a somewhat effective leader on the future of UN peacekeeping operations over a number of years, and is aiming to take up non-permanent membership of the UN Security Council in 2024. On the other hand, Seoul conspicuously failed to open the door to more than a tiny fraction of the Russians who travelled by boat down the east coast of Korea and away from conscription to Ukraine. South Korea is not the only one to make the choice not to allow Russian draft-dodgers in, but it is hard not to conclude that, in spite of its diplomatic commitments, South Korea still struggles a little to play fully the role of wealthy, industrialised participant in what remains of the liberal international order.

Just because the appointment of Prof. Lee was political certainly does not make it wrong. It was a sound decision. However, the background to it raises questions about the Yoon administration’s ability to follow through; that is, to turn words into deeds. There are plenty of people in North Korea, Xinjiang, Russia and elsewhere who will welcome a more assertive and proactive South Korea on this terrain. But only if there is adequate follow-through. And with the Yoon administration sure now to have its focus elsewhere following the tragic loss of more than 150 young lives during Halloween celebrations in the Itaewon area of Seoul, it remains to be seen what will ultimately get done.

Christopher Green is an assistant professor in the Korean Studies department of Leiden University in the Netherlands and senior Korean peninsula consultant for the Brussels-based International Crisis Group. He can be reached at c.k.green@hum.leideununiv.nl or cgreen@crisisgroup.org.