- #China

- #North Korea

- #Sanctions & Human Rights

- #South Korea

► A near-total lockdown imposed by the North Korean Government during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a confluence of pressing global problems, most notably the war in Ukraine, has put human rights, including the human rights situation in North Korea on the backburner.

► The RK’s Government renewed approach towards the DPRK is much needed. Apart from focusing on security and normalization of relations, economic aid, and investment, its humanitarian and human rights objectives would benefit from integrating the COI Report recommendations.

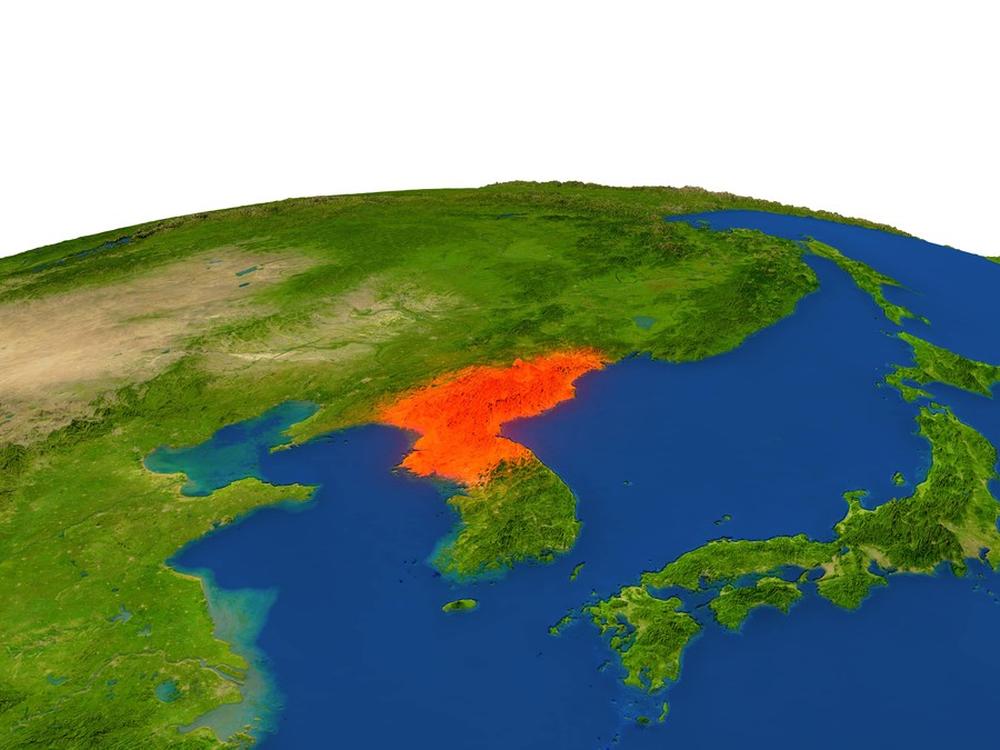

Korean peninsula has been in the eye of Asian crises for more than a hundred years. Long-term and current tensions reflect a series of complex and interlocked issues which can be resolved only through constructive engagement by Pyongyang and Seoul, and – indispensably - China, Japan, Russia, and the US.

The COI Report was meant to give an impetus to developing a new strategy for North Korea. Regrettably, ten years after the COI Report was released the aim to remobilize the international community, including the UN and other international organizations, to take coordinated and responsible action for the renewal of unconditional talks with North Korea has not been reached.

A near-total lockdown imposed by the North Korean Government during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as a confluence of pressing global problems, most notably the war in Ukraine, has put human rights, including the human rights situation in North Korea on the backburner. The advocacy for the protection of human rights as called for in the COI Report has also lost momentum.

As is often the case, the respect for universal human rights has been overshadowed by geopolitical realities. Geostrategic interests are more often than not deaf to the accountability agenda. We live in a time of grave turmoil in the world, new geopolitical divisions, and renewed power politics. All of these have taken a heavy toll on the protection and progress of the human rights agenda, multilateralism, global solidarity, and cooperation.

So, can one still speak of human rights protection in a situation where any kind of respect for human life and dignity has been thrown overboard as we are witnessing in Ukraine and in many other places? A system for the protection of human rights was constructed in the aftermath of World War II and has been developing since. The question is: can it stand the test of time as the world gets overwhelmed by threats unprecedented since 1945?

As an expert body COI did not have many remedies at its disposal. Essentially, it gave a voice to grave concerns and offered suggestions and recommendations to address them. The Commission, hopefully, did raise worldwide awareness about the humanitarian disaster in DPRK. It has also helped bring about some internal policy changes in the economic, trade, and agriculture spheres.

As a member of COI, I would like to add my voice to all those who believe that, despite all impediments, we must persevere. We must not let down thousands and millions of people who have no hope but hope in the goodwill, compassion, and support of the global human rights community. Therefore, the issue of human rights respect and protection in DPRK as well as elsewhere where the situation warrants it must be addressed, notwithstanding the current backsliding, consistently and persistently.

Recent appointments related to the DPRK human rights at the United Nations and in the Government of South Korea as well as the coming commemoration of the 10th anniversary of the U.N. Commission of Inquiry on North Korean Human Rights, open a window of opportunity for President Yoon to reinvigorate the issue. Recently, he has given a number of significant statements in that respect that indicate the importance of the human rights situation in DPRK for his Government.

The United Nations estimates that over 10 million North Koreans, roughly 40% of the population, are undernourished. The Covid-19 pandemic pushed North Korea, one of the poorest countries in the world, further into isolation, aggravating an already grave situation. Instead of opening to cooperation, the DPRK Government launched several missiles, threatening South Korea and the region. According to Andrei Lankov, an expert on the DPRK, Russia's invasion of Ukraine may have boosted Kim Jong-un’s confidence because "it demonstrated that if you have nuclear weapons, you can have almost impunity. And if you don't have nuclear weapons, you're in trouble." He also suspects that “his ultimate dream is to assert their control over South Korea.”

Considering the developments, the RK’s Government renewed approach towards the DPRK is much needed. Apart from focusing on security and normalization of relations, economic aid and investment, its humanitarian and human rights objectives would benefit from integrating the COI Report recommendations.

It is imperative to do utmost to take all stakeholders back to the negotiating table because any further escalation of tensions on the Korean peninsula would add to the current growing threats to stability and peace in the region. There is a lot of anxiety in the world about it.

As far as the negotiating approach is concerned, my long experience in dealing as a human rights defender and a political activist in the aftermath of the collapse of Yugoslavia has taught me to the vital importance of the need for a careful balance between corrective sanctions and constructive engagement. There is ample evidence in modern history that, while targeted sanctions can solve some problems, wholesale sanctions may not do so, and often proved to be, in the long run, ineffective both as the target country and the peace and security in the respective regions are concerned.

I am aware that my position may be controversial, but I strongly believe that the current DPRK Government should be approached in the spirit of a constructive engagement within a peaceful negotiating process, with the aim of a gradual de-escalation of hostilities, the change in its nuclear policies and alleviation of domestic processes.

In writing this, I am not unaware of the fact that the DPR regime would do its utmost to remain in power. Still, while the negotiations proceed, their participation is essential it further nuclear proliferation, aggressive behavior and the suffering of the people is to be avoided.

In this regard, I would like to, once again, stress the importance of the COI Report because, among other things, it did provide the first, fact-based account of gross human rights violations in the DPRK. The Report documented “wide-ranging and ongoing crimes against humanity” and called for “an urgent action by the international community, including referral to the International Criminal Court”.

At some point, the issue of accountability will be addressed both within the perspective negotiating process and the international bodies, and within the DPRK itself. This is where more action is needed. With good reason, accountability is crucial to the promotion of the concept of transitional justice. And the latter is believed to be a major instrument of democratization of totalitarian societies.

The Group of Independent Experts on Accountability, of which I was a member, offered in its report a menu of possible options to take into consideration. The choice is on the North Koreans. It will very much depend on the direction the changes might take.

Additionally, we must bear in mind the legacy of the past which still weighs heavily on the countries in the region and their relations. Historical revisionism, in particular, negatively affects bilateral relations. A great writer wrote that “the past is never dead. It is not even the past.” Getting to grips with history, understanding historical facts, political and social contexts, provide a key to coping not only with the past but with the present as well.

Finally, our knowledge about North Korean society, its values and beliefs is extremely limited. Therefore, it is important to show great cultural sensitivity and “a historical patience”. There are no quick solutions. North Korean society should be given a chance to get prepared for fundamental changes rather than only for a regime change. Proper lessons should be drawn from the failures of imported regime changes in the last 25 years: societal and political progress can take place only if society itself has been ready to embrace them.

I want to believe that reason and wisdom, political courage, will and leadership, and moral responsibility for the common good, peace, and security will prevail. The people in the DPRK deserve to join the world community that strives to ensure, as stated in the UN Chapter, life in freedom from want and fear.

Sonja Biserko is a prominent leader and reformist well- known for her courageous and extraordinary contribution for democratic changes in her country and the region of Southeastern Europe. She is the Chairperson of the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia. Among the founders of the European Movement in Yugoslavia, the Center for Anti-war Action, the Helsinki Committee for Human Rights in Serbia and the Forum for International Relations. Worked on a variety of civil and human rights programs; Helsinki Watch, Lawyers Committee for Human Rights, UN Center for Human Rights, Mazowiecki’s mission and the Tribunal in The Hague. Ms. Biserko organized the first opposition meeting in the former Yugoslavia, Geneva 1991. One of the most strategic projects she has been engaged in was the return of refugees, especially Serbs from Croatia. She was actively engaged in Kosovo issue since 90s. More than ten years engaged in the projects Dealing with Past. She closely worked with Geoffrey Nice’s team on Milosevic’s trial, as well as in other cases in The Hague Tribunal. She has a vast expertise in human rights, peace processes and justice stemming for her visionary political thinking and critical thinking capacities. She was participant in Eric Lane Fellowship, Clare College, Cambridge, UK in 2012, Senior Fellow, US Institute for Peace, Washington D.C. in 2001. She was a member of the UN Commission on inquiry on the DPR Korea 2013-2014.