- #China

- #Global Issues

- #North Korea

- #US Foreign Policy

► China’s anti-US drive is not new, but it has become more virulent and explicit over the last five years. Applicable to the Korean peninsula, China sees the US - not the DPRK - as the biggest troublemaker and accuses the United States of instigating conflicts across the globe.

► The recent rapprochement attempts between Tokyo and Seoul, as well as the adoption under the Yoon administration of an Indo-Pacific strategy, is seen extremely negatively and is likely that Beijing will retaliate against South Korea’s moving closer to Washington.

► Beyond the short-term retaliation risks, the biggest, long-term strategic issue for South Korea when it comes to China lies in the fact that whatever Seoul will do, and independently of the administration in place, ROK will still be seen in Beijing as much less of a natural partner than the DPRK, just because it is an ally of the US.

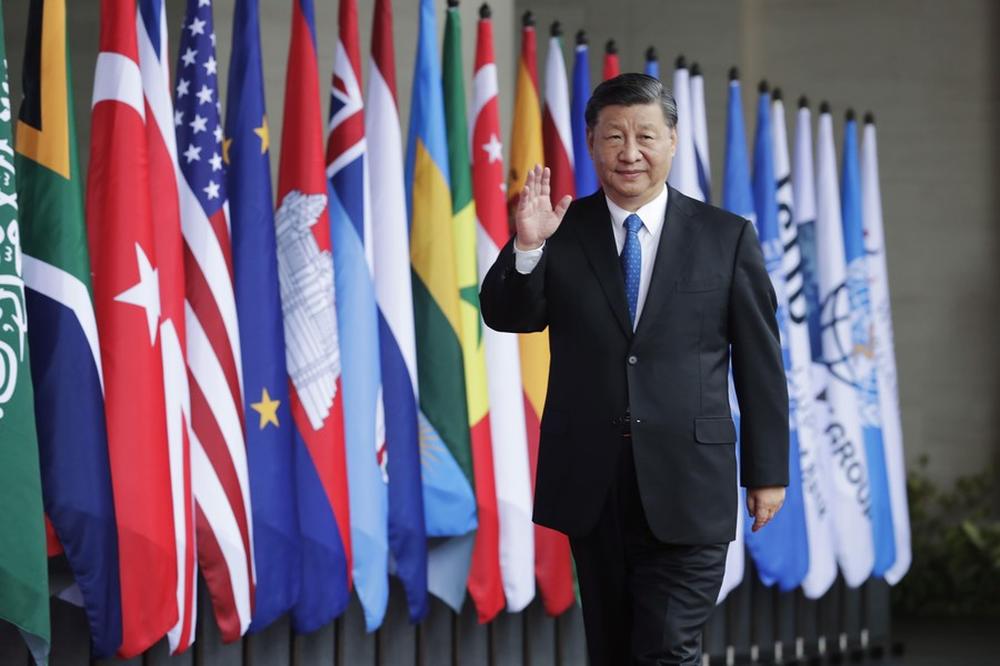

China’s strategy in Asia and beyond is first and foremost driven by its rejection of the US presence and influence, which it considers illegitimate. China’s anti-US drive is not new, but it has become more virulent and explicit over the last five years. In a report published in February 2023 by the Chinese foreign ministry entitled ‘US Hegemony and Its Perils’, China accuses the United States of instigating conflicts across the globe. China is not only discrediting the US and its allies as a source of sustainable security, but also is bluntly accusing them of being the main source of insecurity. This rhetoric applies to the war in Ukraine, for which Chinese officials are explicitly blaming the US, accusing Washington of ‘fanning the flames’ in Ukraine and of having a vested interest in the continuation of the war. It also applies to the Korean peninsula, where China sees the US - not the DPRK - as the biggest troublemaker. On July 14 at the United Nations Security Council, the Chinese envoy warned against military pressure on the DPRK in these terms: “We are (…) concerned about the heightened military pressure and repeated dispatches of strategic weapons by a certain country to carry out military activities on the Korean Peninsula”. The Chinese government emphasizes the “legitimate security concerns” of the DPRK (an expression also used to support Russia), and explicitly condemns sanctions that are taken against the country (as much as sanctions taken against Russia). As China-US rivalry deepens and the world becomes more polarized, China is more clearly identifying the countries that it considers part of its “circle of friends” (朋友圈), and they include both Russia and the DPRK, along with other countries such as Iran. It is not by chance that China and Russia are aligned at the United Nations when it comes to the DPRK: both countries vetoed a draft resolution in the Security Council on May 26, 2023, aimed at tightening the sanctions regime against Pyongyang. Even though these countries continue to share a limited number of divergences, their common antagonism against the US and their common desire to see an emerging post-western security order is a strong driver for reinforced cooperation in the long term.

These countries also share a strong rejection of NATO. More than that, China perceives NATO as an enemy for both historic and new reasons: the 1999 bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade, the identification of China as a challenge in NATO’s new Strategic Concept, the plan (now apparently shelved) to open an liaison office in Tokyo, and the participation of the organisation’s four Asia-Pacific partners (South Korea, Japan, Australia and New Zealand) at the Madrid and Vilnius NATO Summits. Beijing also sees the ‘US-led Indo-Pacific strategy’ as a way to establish “an Asia-Pacific version of NATO” that is “bound to fail”, according to official statements. As seen from Beijing, any country which is adopting an “Indo-Pacific strategy” is illegitimately siding with the US.

The concept paper on China’s ‘Global Security Initiative’ (全球安全倡议 - GSI), issued in February 2023, explicitly advocates a ‘new vision of security’ to turn the page of the existing security order considered by Beijing as illegitimately led by the West, and first and foremost, the US. From a purely security perspective, China’s ambition to compete with the US-led alliance system in the region and promote a post-alliance regional order appears unrealistic at this point in time given the asymmetric military capabilities (naval capabilities in particular) and the structural role that the US alliance system continues to play in Asia. But the diverse array of China’s partnerships in the region, including economic and technological partnerships, tends to blur the lines of the US regional influence. Most countries with strong security relations with the United States, including Japan and South Korea, continue to maintain strong economic and technological ties with China. In this context, China is aware that it has leverage to voice its discontent when countries of the region reinforce their security ties with the US.

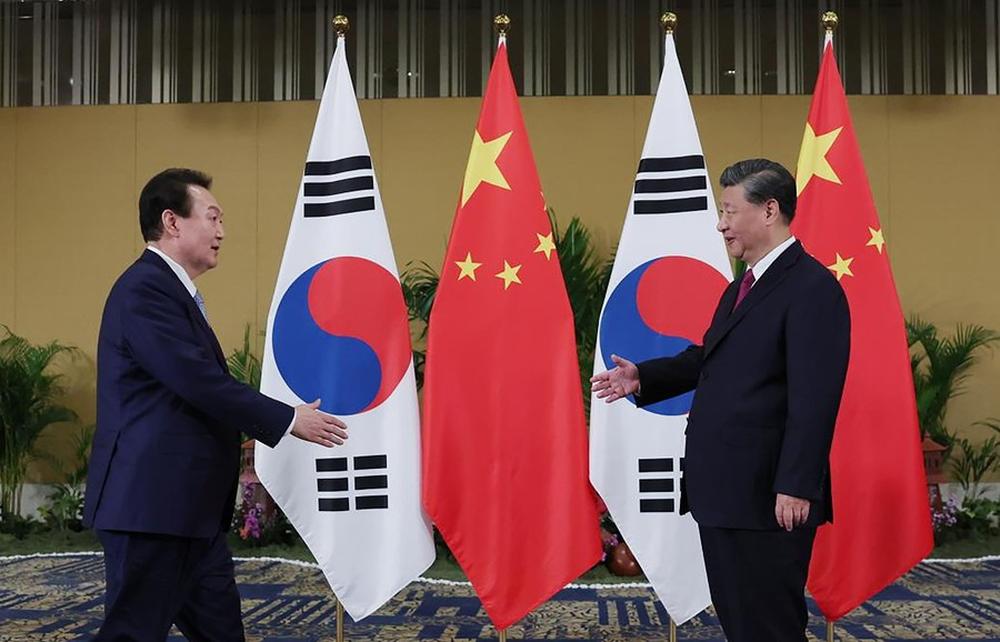

The recent rapprochement attempts between Tokyo and Seoul, as well as the adoption under the Yoon administration of an Indo-Pacific strategy, is seen extremely negatively in Beijing. To some extent, given the known divergences of foreign policy approaches between political parties, the alternance of the ROK government was expected to lead to a rapprochement with the US ally and a change of approach towards China. But the regional and international context has changed, and the virulent anti-US/Western drive observed in Beijing lead to stronger stances towards the US and also towards its allies.

In this context, it is likely that Beijing will retaliate against South Korea’s moving closer to Washington, in stronger terms than in 2017 after Seoul’s decision to allow the United States to deploy a Terminal High Altitude Air Defense (THAAD) battery on the national territory. Such retaliation may take place following positions or decisions adopted in many different areas: over reinforced security cooperation with the US, declarations on Taiwan or on Human Rights, and other issues seen as politically sensitive. Sanctions could be strictly economic, but also technological, or a mix of both. Since the THAAD retaliation in 2017, China deployed and tested the effects of its sanction policy towards various countries and in many ways. First and foremost, towards the US, but also for instance Australia. From May 2020, following the deterioration of the political relationship between Canberra and Beijing, China blocked the import of roughly a dozen Australian goods for which China was the major market, cutting imports worth around US$13.4 billion annually. At the global level, recent restrictions taken by China in the field of semiconductors (such as on the exports of gallium and germanium- two metals key to the manufacturing of semiconductors) show that China is fully ready to use its leverage in key strategic sectors and materials.

But beyond the short-term retaliation risks, the biggest, long-term strategic issue for South Korea when it comes to China lies in the fact that whatever Seoul will do, and independently of the administration in place, ROK will still be seen by Beijing as much less of a natural partner than the DPRK, just because it is an ally of the US. It becomes as simple as that at a time of a strong anti-US driven Chinese foreign policy. Seoul should have no illusion about Beijing’s willingness to pressure the DPRK or contain the development of its nuclear program. On the contrary, Beijing will likely continue to be diplomatically active, at bilateral and multilateral levels, in cooperation with other countries including Russia, to limit as much as possible the pressure exerted on Pyongyang.

Dr. Alice Ekman is Senior Analyst of charge of the Asia portfolio at the European Union Institute for Security Studies (EUISS).