- #Japan

- #Multilateral Relations

- #US-ROK Alliance

► The Camp David agreement is a strategic step forward towards a more integrated and collective system of defense that contributes significantly to the national security of the ROK and its two partners

► The key challenge will be continuing to actively implement the agreements even when disputes inevitably arise between the Seoul and Tokyo. Military, intelligence, economic, and development cooperation should be normal activities, not hostage to politics.

► Embedding bilateral progress between Seoul and Tokyo in the framework of trilateral cooperation can serve as a buffer against future downturns in Japan-ROK relations that helps safeguard the well-being of the three countries.

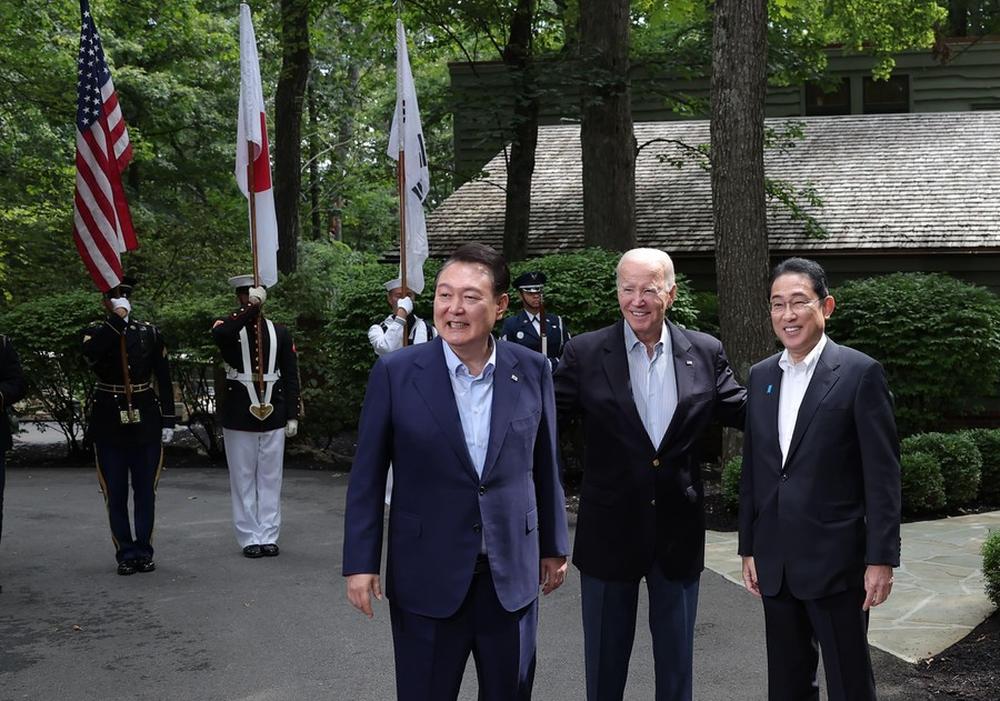

Presidents Biden, Yoon, and Prime Minister Kishida, accompanied by only a handful of top aides, spent Friday, August 18 at the wooded presidential retreat in the Maryland mountains, Camp David, for a day of extended bilateral talks, trilateral meetings, and informal activities. The summit was significant, not only because it was the first stand-alone summit of the three leaders, but because it yielded groundbreaking commitments and cooperative initiatives that benefit all three nations and ultimately the region.

Holding the Summit at Camp David is significant because it is an iconic and sparingly-used venue with a historic tradition that conveys the importance of the trilateral partnership to domestic and foreign audiences. The choice of venue reflects the depth of Biden’s determination to forge progress in the relationship between America’s two key allies in Northeast Asia. The retreat carries echoes of the 1978 Camp David Accords, where then-President Jimmy Carter helped broker a peace deal between the leaders of Israel and Egypt after decades of violence and war. Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill held talks in the same rustic cabins used for this meeting.

The Camp David setting – without neckties or interruptions -- allowed for relaxed and informal interaction – an environment that will help nurture the personal relationship between Yoon Suk Yeol and Fumio Kishida. Yoon’s remarkable political courage in taking the initiative to break the stalemate with Japan has earned well-deserved praise from around the world. Less apparent, but also important, is the skill with which the Japanese Prime Minister has managed his own politics to reciprocate and build on the positive momentum created by the Korean president.

The pace of change – of progress – is extraordinary. For decades, the U.S. has operated under the burden of bitter estrangement between its two strongest allies in East Asia – a dynamic that has complicated the task of deterring and defending against threats from North Korea and beyond. Then-President Obama hosted two trilateral summits with his counterparts from Japan and Korea on the margins of multilateral meetings in 2014 and 2016. The progress achieved there, as well as the bilateral achievements between Seoul and Tokyo, were reversed by the subsequent Korean government, which showed a mix of deference to China, antagonism towards Japan, and ambivalence towards the United States. Under pressure from China, the Moon Jae-in administration acceded to the so-called “Three Noes” pledge. Those concessions failed to diminish China’s support for North Korea and instead convinced Beijing that South Korea could be bullied into compromising its national security interests.

In sharp contrast, the Camp David agreement is a strategic step forward towards a more integrated and collective system of defense that contributes significantly to the national security of the ROK and its two partners. The “Commitment to Consult” is an agreement that an attack against any one of the countries has direct implications for the security of all three and that all have a “duty consult” one another in a crisis. While this is not a NATO-type treaty obligation, it constitutes a significant step to deepen and expand trilateral security cooperation covering a range of defense and economic areas. And while the trilateral structure is not a three-way alliance, it is a strategic partnership arrangement capable of responding to a wide array of challenges from North Korea, China, and Russia.

“The Commitment to Consult” is a political agreement, rather than a treaty, but it and the “Spirit of Camp David” statement are powerful documents that set the course and create momentum for trilateral cooperation going forward. The leaders’ joint statement explicitly emphasizes the importance of “leveraging the unique capabilities” of each nation. Key outcomes include annual meetings among leaders as well as Foreign Ministers, Defense Ministers, Commerce Ministers, and National Security Advisors. In defense, the leaders agreed on a multi-year and multi-domain trilateral exercise plan, cooperation on ballistic missile defense, a working group to combat DPRK cyber threats, enhanced real-time intelligence sharing, and a process for countering foreign disinformation. The three countries will align their defenses against intellectual property theft, economic coercion, and the misuse of surveillance systems. A senior Indo-Pacific Dialogue will help coordinate policies and deepen partnerships with Southeast Asian and Pacific Island Countries, and other mechanisms will bolster cooperation in development assistance, disaster relief, and maritime security. The agreements deepen economic cooperation and areas such as women’s empowerment and supply chain protection, and in science and technology, public health, and youth exchange.

Security cooperation is a key element of the trilateral partnership. But the spectrum of combined cooperative initiatives in areas beyond defense and intelligence — such as development, health, economics, and governance — are immensely valuable investments and reflect the broad overlap of interests and values among the three countries.

The work program coming out of Camp David also reflects the fundamental and pivotal role that technology plays in the national and economic security of the three countries. The leaders recognize the extent to which tech cooperation among them will contribute to the stability of the Indo-Pacific given the respective technological strengths and the roles in the region of each nation. They will work on developing early warning systems to guard against supply chain disruptions, implement controls to prevent the theft or misuse of sensitive technologies and research, and increase access to the STEM talent required for technological competitiveness.

The trilateral summit took place against the backdrop of the imminent threat of yet another North Korean intercontinental ballistic missile launch, Chinese and Russian warships operating jointly close to Japan, and tensions across the Taiwan Strait. Revisionist autocracies such as North Korea, Russia, and China increasingly are working together to challenge the rules-based order and to sow divisions among western democracies. The reactions to the Camp David Summit from Beijing, Pyongyang, and Moscow have been typically hostile -- denouncing “exclusive cliques,” “bloc confrontation,” and warning of an “Asian mini-NATO” – even as they themselves band together and despite the fact that it is their countries who threaten – or in one case, invade – their neighbors.

However, the simple fact is that more effective deterrence adds to regional security. At Camp David, President Yoon made the point that “challenges that threaten regional security must be addressed by us building a stronger commitment to working together,” and that “stronger coordination between Korea, the U.S., and Japan requires more robust institutional foundations.”

The steps taken by President Yoon in extending a hand to Tokyo, the constructive response by Japanese Prime Minister Kishida, and the strong support of President Biden have brought the trilateral relationship to a high point at Camp David. But as important as the summit proved to be, the real test will be the sustainability of the agreements and the follow through in the ambitious trilateral agenda. Trilateral cooperation is a process, and it will take more than this summit to build a durable Korea-U.S.-Japan partnership that does not depend on a particular leader.

The key challenge will be continuing to actively implement the agreements even when disputes inevitably arise between the Seoul and Tokyo. Military, intelligence, economic, and development cooperation should be normal activities, not hostage to politics. Regular meetings between leaders and officials, defense exercises, intelligence sharing mechanisms, and a variety of exchanges and working groups can help sustain such cooperation going forward. Progress in the workstreams outlined at Camp David will help ensure that cooperation can be sustained beyond the leadership terms of the current leaders. Embedding bilateral progress between Seoul and Tokyo in the framework of trilateral cooperation can serve as a buffer against future downturns in Japan-ROK relations that helps safeguard the well-being of the three countries.

Now that the Camp David Summit is over, Yoon, Kishida, and Biden must all find ways to prove the value of the agreements to their domestic audiences. All three leaders have important political contests in the coming months –Korean national assembly elections in the spring, possible snap elections in Japan, and the presidential campaign in the United States. The political calendar, therefore, requires that they make progress and consolidate it in ways that can endure through their upcoming electoral processes and beyond.

Daniel Russel is Vice President for International Security and Diplomacy at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI). Previously he served as a Diplomat in Residence and Senior Fellow with ASPI for a one year term. A career member of the Senior Foreign Service at the U.S. Department of State, he most recently served as the Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs. Prior to his appointment as Assistant Secretary on July 12, 2013, Mr. Russel served at the White House as Special Assistant to the President and National Security Council (NSC) Senior Director for Asian Affairs. During his tenure there, he helped formulate President Obama’s strategic rebalance to the Asia Pacific region, including efforts to strengthen alliances, deepen U.S. engagement with multilateral organizations, and expand cooperation with emerging powers in the region. Prior to joining the NSC in January of 2009, he served as Director of the Office of Japanese Affairs and had assignments as U.S. Consul General in Osaka-Kobe, Japan (2005-2008); Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in The Hague, Netherlands (2002-2005); Deputy Chief of Mission at the U.S. Embassy in Nicosia, Cyprus (1999-2002); Chief of Staff to the Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs, Ambassador Thomas R. Pickering (1997-99); Special Assistant to the Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs (1995-96); Political Section Unit Chief at U.S. Embassy Seoul, Republic of Korea (1992-95); Political Advisor to the Permanent Representative to the U.S. Mission to the United Nations, Ambassador Pickering (1989-92); Vice Consul in Osaka and Branch Office Manager in Nagoya, Japan (1987-89); and Assistant to the Ambassador to Japan, former Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield (1985-87). In 1996, Mr. Russel was awarded the State Department's Una Chapman Cox Fellowship sabbatical and authored America’s Place in the World, a book published by Georgetown University. Before joining the Foreign Service, he was manager for an international firm in New York City. Mr. Russel was educated at Sarah Lawrence College and University College, University of London, UK.