- #China

- #Economy & Trade

- #Global Issues

► What is worse, Russia’s war with Ukraine has increasingly isolated itself from the world, making it unlikely to become a rising economic star on the global stage.

► Indeed, the driving factor that unites BRICS countries is their common dissatisfaction with the existing international system, rather than a shared proposition about how to reform the system.

► These alternatives give China the option to walk away should BRICS fail to satisfy its diplomatic ambition.

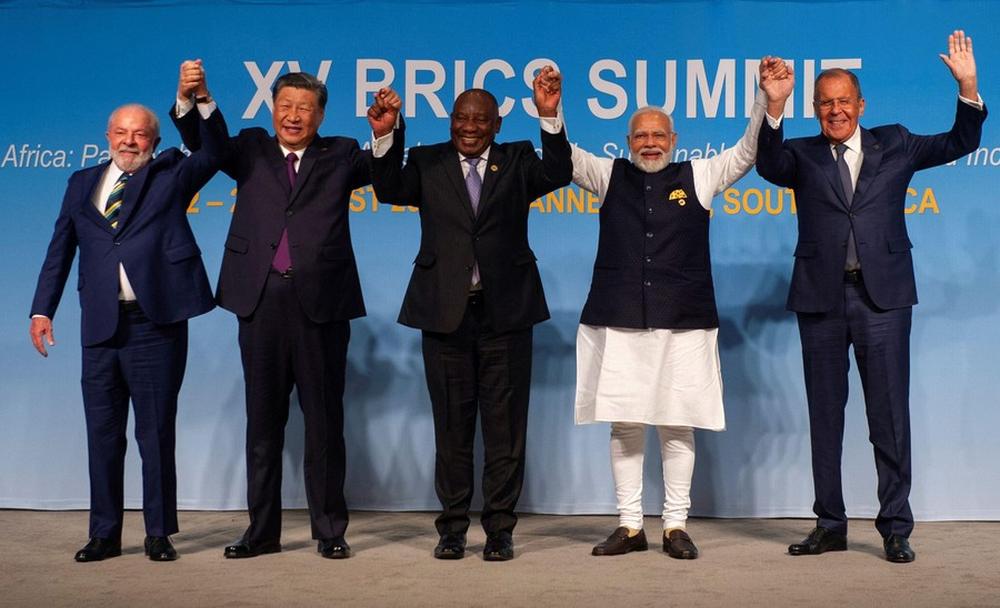

The BRICS summit in South Africa and the expansion of BRICS membership have recently attracted considerable media and policy attention. Many analysts situate the move within the context of U.S.-China competition and consider it a big diplomatic win for China as well as a substantial blow to American power. The development of BRICS is thus viewed as a sign of an emerging new Cold War-like or an alternative world order, which will make a significant challenge to the existing U.S.-led world order. This view has perhaps gone too far.

In order to understand the current BRICS, it is important to briefly review its origin and what has been achieved thus far. When Goldman Sachs Chief Economist Jim O’Neill first proposed the concept of BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) in 2001 (later joined by South Africa in 2010), he envisioned a group of rising powers and continuous economic growth, which would drive significant developments in globalization and post-Cold War international system. More than two decades later, however, BRICS as a group has not made much progress in achieving the vision set out in the early 21st century. Besides the arbitrary and somewhat accidental nature of the grouping by Jim O’Neill, there are several reasons for this.

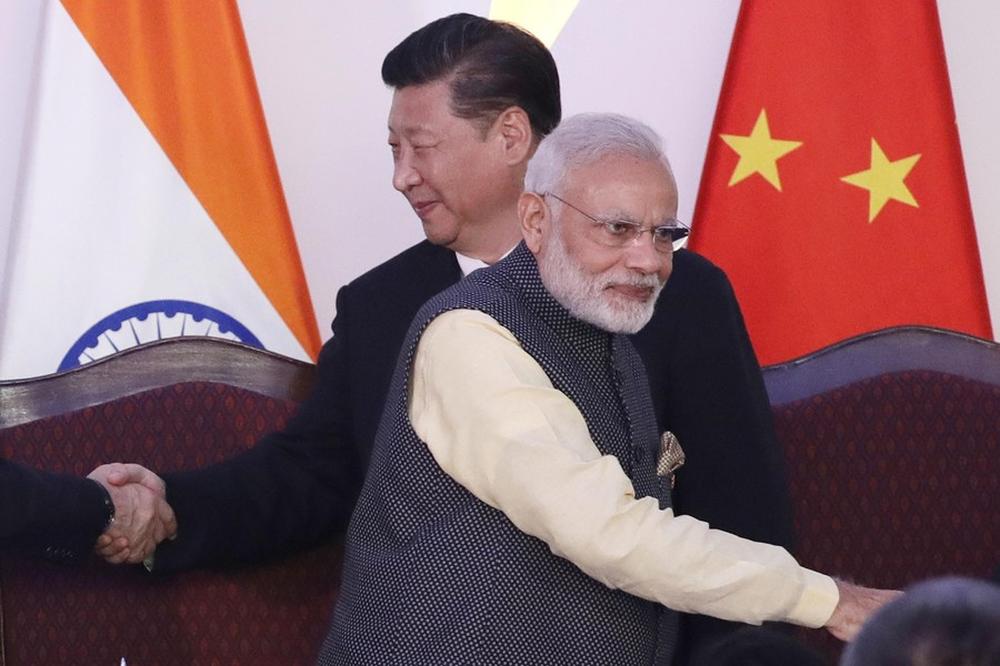

To start with, economic landscapes look quite different from when BRICS was initially considered as a group of rising stars. The economic growth of Brazil, Russia, and South Africa have not performed at a satisfactory level to sustain the original prophecy due to domestic economic and political problems. What is worse, Russia’s war with Ukraine has increasingly isolated itself from the world, making it unlikely to become a rising economic star on the global stage. This has left India and China as the only hopeful rising stars. Nonetheless, it remains a question as to what extent their growth is sustainable. Even for China, the most significant economic actor in BRICS, signs of a slowdown have emerged for years due to considerable economic difficulties, ranging from house bubbles, an aging, and declining population to unfavourable international environment. The growing geopolitical tension between these two hopeful economic stars, India and China, has also been concerning.

The contemporary economic phenomena of BRICS as a group have largely lost their touch compared to what was envisioned when it was coined. This has challenged the very purpose of BRICS as a useful concept and, consequently, what it stands for. This question becomes inevitable when discussing BRICS expansion. Indeed, instead of injecting fresh energy into BRICS to drive the world’s economic future, some new candidates of the expansion appear to be more of an economic burden than a hope for the future. From Argentina (the IMF’s biggest borrower and a serial defaulter), Egypt (the IMF’s second largest debtor) to Ethiopia (who recently survived from a two-year civil war), those countries have been grappling with various domestic economic crises for quite some time. If BRICS as a group no longer represents a rising and growing economic force, then is it, and what does it stand for?

This context has made China’s role rather important, as many new candidates associate the benefits of BRICS membership with closer economic ties with China. Needless to say, China championed BRICS expansion for a reason. A group of non-Western countries standing together with China can help counter American containment of China’s rise. Greater economic integration within BRICS countries, for example, will assist China in offsetting the U.S. efforts in the so-called decoupling or de-risking, whatever slogan it may be called. Tangible economic outcomes, such as the use of Chinese currency in trade among BRICS countries, are already evident. From this perspective, BRICS expansion will allow China greater economic access to non-Western markets, and provide strategic leverage to compete with the U.S.

Nonetheless, what China can achieve from this group is also limited – largely due to the lack of cohesion and coherence. Indeed, the driving factor that unites BRICS countries is their common dissatisfaction with the existing international system, rather than a shared proposition about how to reform the system. In the past few decades, despite their economic growth, many Global South countries believe that they are marginalized in the U.S.-dominated global order – their voting power in global economic institutions, for example, has not grown to reflect the expansion of their economy. Not surprisingly, BRICS countries often express frustration that their preferences and interests are underrepresented or ignored, leading to initiatives such as BRICS Development Bank (now renamed as The New Development Bank) and Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank.

When it comes to specifics beyond this common frustration, however, there is a lack of coherent BRICS position. Over two decades after the idea was proposed, BRICS has yet to formulate a blueprint for addressing the shortcomings of the current international system and an alternative vision of a new international system. To be fair, the disagreements and tensions among BRICS are largely responsible for this failure. The most obvious example is the geopolitical tension between the two largest BRICS countries, China and India, which range from border conflicts to competition for dominance in the region and beyond. For example, while many BRICS countries are enthusiastic about China’s Belt and Road Initiative (Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy slogan) that spans across Global South countries, India openly voices its opposition and refuses to join the initiative due to geopolitical concern especially about China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, a flagship program of the Belt and Road Initiative. India-China competition over dominance and leadership will no doubt spill over into to BRICS framework. It has also become evident that India and China have different agendas and visions for BRICS. For instance, while Russia and China hope to develop a closely-knit group to counter American influence, India and Brazil (who are American partners) are concerned about BRICS becoming too anti-West or anti-America. After all, India, for example, is a critical part of Washington’s Indo-Pacific strategy to contain China. In this regard, the analyses that consider BRICS as a direct rival to American leadership remain to be tested.

If disagreements among the group of five are already challenging to accommodate, BRICS expansion would only intensify the problem about coherence and cohesion. From new members with American partnership (such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE) to those with geopolitical rivalries (such as Iran and Saudi Arabia), the expansion will undoubtedly create more complicated interests and diverse diplomatic goals to be accommodated.

Even if those issues can be overcome with more financial and diplomatic resources, we should not take for granted that China is always willing to pay the price. The slowdown of the Chinese economy made it more reluctant to do so, as seen in declining investments in the Belt and Road Initiative. But more importantly, China has other organizations, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the Shanghai Cooperation Organization that can help China to achieve many of its goals like BRICS. These alternatives give China the option to walk away should BRICS fail to satisfy its diplomatic ambition. Furthermore, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization can offer a level of security cooperation forum similar to NATO, which is unlikely to be achieved within BRICS framework. To form a proper Cold War-like grouping, security reassurance, as the Soviet Union provided to its allies, is essential. At the moment, China neither has the willingness nor the military capacity to project its security power beyond East Asia. Even if China were to do so, the more likely platform would be the Shanghai Cooperation Organization rather than BRICS, given the problems discussed.

Not surprisingly, China’s motivation in advocating for BRICS largely stems from the strategic pressure from the U.S. Should there be an improvement or stabilization of U.S.-China relations – which I sincerely hope – the value of BRICS to China will decrease accordingly. After all, the majority of China’s external trade is still conducted with the U.S. and its Western allies. What BRICS countries can offer to China is some level of offset instead of a full replacement of the Western market. In this regard, China’s push to BRICS is far from unconditional.

Above all, while the recent developments within BRICS represent a sign of an emerging group and potentially something different from the West-led G7, it is too early to become overly excited or anxious about the move. BRICS still faces considerable challenges, whether it no longer represents a growing economic powerhouse, demonstrates an acceptable level of solidarity to be an effective organization, or how to manage its relations with the West, especially the U.S. Unless these challenges are addressed, BRICS as a group is unlikely to make a significant impact on changing the existing global order.

Jinghan Zeng is Professor of China and International Studies at Lancaster University. His research lies in the field of China's domestic and international politics. He is the author of Artificial Intelligence with Chinese Characteristics: National Strategy, Security and Authoritarian Governance (2022), Slogan Politics: Understanding Chinese Foreign Policy Concepts (2020) and The Chinese Communist Party's Capacity to Rule: Ideology, Legitimacy and Party Cohesion (2015). He is also the co-editor of One Belt, One Road, One Story? Towards an EU-China Strategic Narrative (2021). He has published over twenty refereed articles in leading journals of politics, international relations and area studies including The Pacific Review, Journal of Contemporary China, International Affairs, JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies and Third World Quarterly. He draws on his research to connect with audiences beyond academia. He frequently appears in TV and radio broadcasts including the BBC, ABC Australia, Al Jazeera, Voice of America, DR (Danish Broadcasting Corporation), Russia Today (RT), China Central Television (CCTV) and China Global Television Network (CGTN). He has been quoted in print/online publications including Financial Times, Forbes, South China Morning Post, PULSO and TODAY. He has written op-ed articles for The Diplomat, BBC(Chinese), The Conversation, Policy Forum among others.