- #China

- #Europe

- #Global Issues

► Once China opened up again to the world after the COVID-19 pandemic, the EU updated its strategy towards China.

► Although EU-China policy is criticized for lacking consistency among its member states, there is a widespread consensus on some key points:

i) China is a partner, competitor, and rival, so the EU must build a constructive relationship with it.

ii) The degree of China’s support in Ukraine is a key determinant of the level of trust among EU leaders.

iii) EU member states should put more emphasis on shaping the international human rights regime.

► The European diplomacy must cooperate with other like-minded countries in the region, particularly South Korea and Japan, to reduce risks derived from overdependence on China.

► However, the biggest unresolved question for the EU-China strategy is whether the EU can maintain an autonomous China policy if Trump comes back.

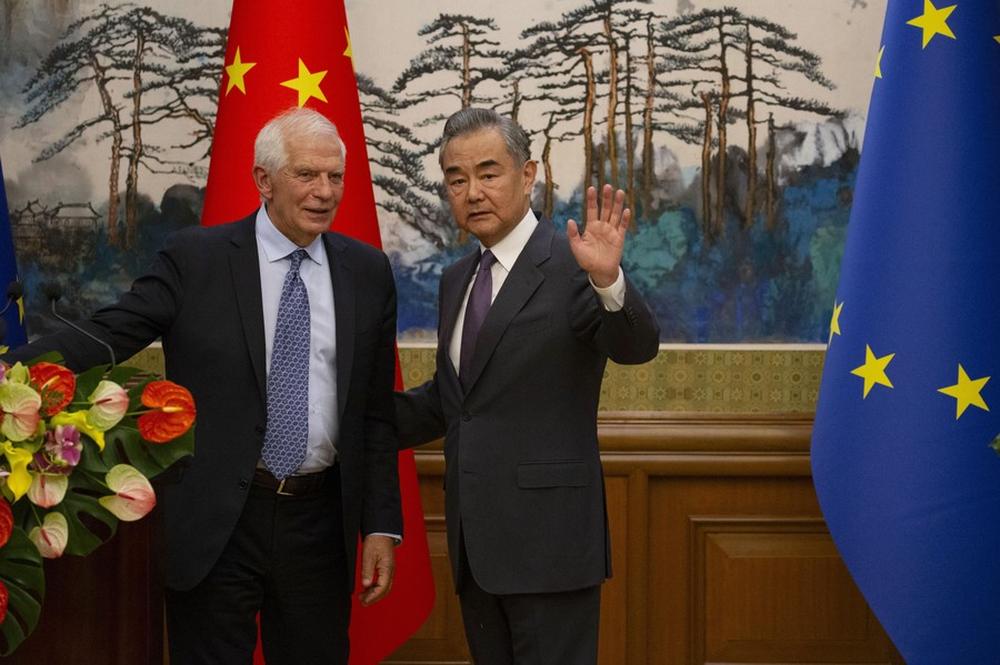

The EU strategy towards China is based on a document published in March 2019, EU-China – A strategic Outlook, which describes this country as a partner, competitor, and systemic rival. This paper became outdated quickly due to important subsequent events, in particular, the Covid-19 pandemic and China's response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The first evidenced the EU's overdependence on China in essential products such as medicines and health equipment and supplies; and the second how the existing geopolitical gap between Beijing and the EU could affect European security dramatically. Hence, once China opened up again to the world after abandoning its Dynamic Zero-COVID Policy, the EU embarked on an update of its strategy towards this country.

Despite much criticism on EU-China policy for the lack of consistency among its member states, there is a widespread consensus on some key point for its renovation. China is a partner, competitor and rival and therefore, even if rivalry is gaining momentum, it is in the interest of the EU to have a constructive relationship with China, since this country offers many economic opportunities and is a key partner for tackling central issues of the global agenda such as climate change, pandemics, non-proliferation of weapons of mass destruction and macroeconomic stability. More specifically, there is agreement to give more importance to security within the entire relationship with China and to focus actions in the field of values on specific issues where the EU can have a clear impact.

Regarding security, China's posture in Ukraine mediates the whole EU's stance towards the Asian country. The degree of Chinese support for Russia or for a solution to the war in line with Ukrainian positions is key to determining the level of trust of the EU leaders, but Viktor Orban, in China and, therefore, conditions the relationship of their countries and the whole of the EU with China. In addition, economic security is playing a growing role in EU's considerations of their economic linkages with China to the point that de-risking became the new mantra for defining the bilateral relation in Europe. Even if the EU economic security strategy released in June is country agnostic, there is ample concern in Brussels and European capitals about excessive dependence on Chinese providers for raw materials needed for the green and digital transition and about the damage on the welfare of European citizens derived from the unbalanced playing field for economic relations with China. When it comes to values, the agreed change is to put more emphasis on countering the efforts of Chinese diplomacy to shape the international human rights regime according to its preferences and to make sure that companies operating in Europe, including non-EU companies respect Human Rights.

Nevertheless, there are significant differences between European leaders that will substantially condition the concretion and implementation of an updated EU China strategy. As we saw last spring during the joint visit that Macron and Von der Leyen made to China, the traditional division of labour between the member states and the Commission remains in force. The former act as good cops and focus on addressing issues that they consider beneficial to them, while the Commission plays the bad cop role and addresses issues that the member states do not want to discuss bilaterally to avoid negative repercussions for their national corporate sector.

Another factor hindering a coherent China strategy in the EU is the materialist-postmaterialist divide. The former tend to pay more attention on the impact of EU-China relations on economic growth and employment in Europe, whereas the latter give priority to their effect on human rights and democracy in China and Europe. Indeed, the economic clout of China inside the EU is not evenly distributed among its member states. According to the Financial Times, the percentage of the GDP of the four largest EU economies that depends on China is 10 percent in Germany, 5 percent in France, 2 percent in Italy and 1 percent in Spain. Although materialist positions have been and continue to be predominant among European authorities, the population favours the post-materialist approach. According to a Pew Research Institute study from June 2022, human rights is the issue the EU citizens are most critical of when evaluating China and, in all member states but Hungary, a majority of the population prefers promoting human rights in China at the expense of economic relations over strengthening economic ties without addressing human rights. The interest of the Chinese shipping company COSCO in acquiring a minority stake in the Hamburg port offered an illustrative example of how this cleavage affects European considerations on economic security vis-á-vis China as chancellor Scholz gave green light to the deal despite the opposition of the Greens and the Free Democrats, the two minority parties that are part of his government.

This is not to mention the cleavage between liberalism and interventionism. The growing number of instruments that the EU has provided itself with to regulate its foreign economic relations and the strengthening of its industrial policy are evidence of the increasing influence of interventionist positions within the EU, including its policy towards China. However, important differences remain between countries favorable to more state intervention, such as France, and those more reluctant, such as the Netherlands and the Scandinavians. This division will condition the implementation of the economic security strategy, for example, the characteristics of an eventual outbound foreign direct investment mechanism.

Finally, it must be considered that European diplomacy looks towards other countries when updating its approach towards China. This is only natural considering the huge geostrategic implications of EU's relations with Beijing and that diversification is a key concept when reducing risks derived from overdependence on China. This opens multiple opportunities for collaboration with other countries in the region, as evidenced by EU initiatives such as its Indo-Pacific Strategy and Global Gateway. Furthermore, it should be noted that this incipient diversification process takes places in a context of fast increasing cooperation with likeminded countries in the region, in particular South Korea and Japan, even in traditionally little explored areas such as security and defense. It is also important to mention the enormous potential of relations with India for contributing to European strategic autonomy and security, although its materialization, despite the establishment of the EU-India Trade and Technology Council in April, is much more complex than with Seoul and Tokyo. But, unfortunately, looking to the future it is not all opportunities. The EU and the US have substantially aligned their strategy towards China during the Biden administration, but the continuity of this coordination depends on who is the next president of the United States. Paradoxically, after November 2024, the biggest risk to a constructive and balanced relationship between the EU and China may not be in Beijing or Europe, but in the US. The biggest unresolved question for the EU-China strategy is whether the EU can maintain an autonomous China policy in a context of high antagonism between Beijing and Washington as it could be expected if Trump comes back to the White House. Let's hope we will not be forced to find out.

Mario Esteban (@wizma9) is Full Professor at the Centre for East Asian Studies (Autonomous University of Madrid) and Senior Analyst at Elcano Royal Institute. His last book is China and International Norms: Evidence from the Belt and Road Initiative (Routledge, 2023).