- #Japan

- #Multilateral Relations

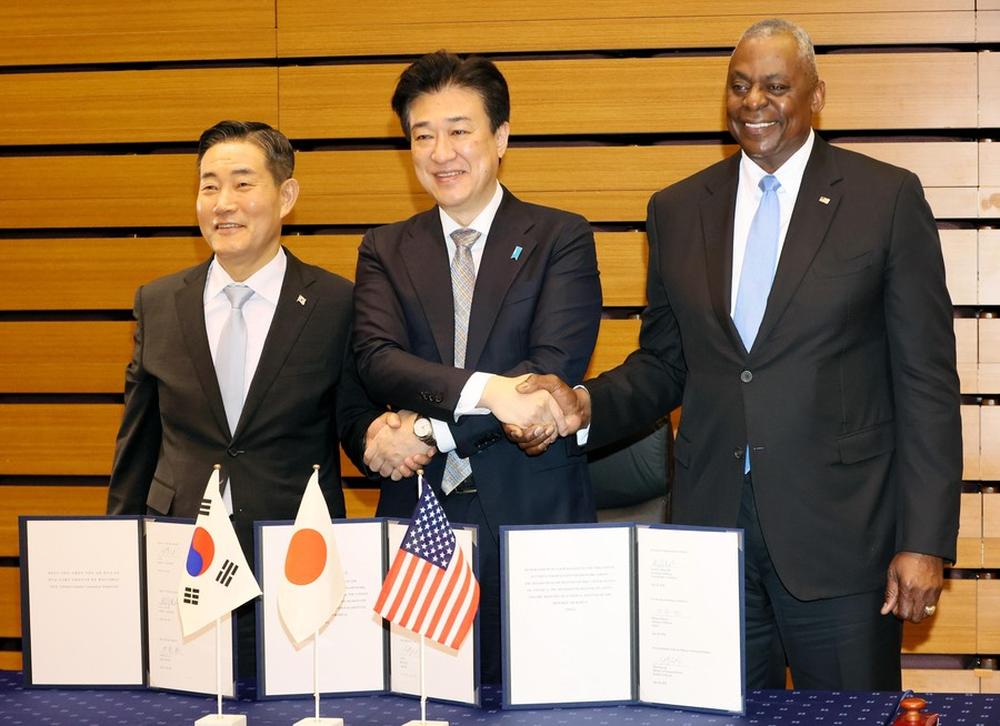

- #US-ROK Alliance

► Challenges in Japan-ROK Relations: Leadership changes in both Japan and South Korea pose risks to their improving security cooperation, with concerns over historical issues and political agendas.

► Japan-Australia Model: The Japan-Australia security partnership offers lessons for Japan-ROK cooperation, showing how institutionalized and comprehensive collaboration can endure despite leadership changes.

► Future Cooperation: Japan and South Korea should build a shared vision for the Indo-Pacific, institutionalize security cooperation, and gain bipartisan support to ensure lasting relations.

Despite recent improvements in Japan-ROK security cooperation, many challenges and uncertainties remain in the relations between the two countries. The most significant concern is the possibility of another setback in relations due changes in government or leadership.

In South Korea, some are concerned about whether Shigeru Ishiba, who became Japan’s new Prime Minsiter in October 2024, will continue to be able to manage bilateral relations. Ishiba’s views on history are regarded favorably in South Korea, but some are wary of his conservative and ambiguous political agendas, such as establishing a “national defense military” and “Asian-NATO.” Divisions inside the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and the growing influence of more conservative politicians, such as Sanae Takaichi, are another potential source of concern.

Meanwhile, many Japanese are concerned that a leadership change in South Korea could lead to a relitigation of historical and territorial disputes and once again result in a downturn in relations between the two countries. Such concerns have worsened amid a weakening of the Yoon administration’s domestic political support in part due to the ruling party’s historic defeat in South Korea’s National Assembly general election in April 2024.

Against this backdrop, what initiatives will be needed to establish more a sustainable bilateral relationship that can withstand government and leadership changes in the two countries?

To answer this question, it may be worth taking a closer look at the important lessons from the case study of security cooperation between Japan and Australia. Since the end of the Cold War, Japan and Australia have consistently strengthened their security partnership. The relationship was sustained, and even became stronger despite leadership changes in the two countries. In October 2022, Japan and Australia renewed the Joint Declaration for Security Cooperation, which was originally announced in March 2007. In Japan, it has increasingly become common to describe Australia as Japan’s “quasi-ally” or de-fact ally without an official mutual defense treaty.

Importantly, this has not been for a lack of “historical issues” between the two countries. The bombing of Darwin by Japanese forces during World War II remains prominent in the public conscience of Australia, particularly among older generations. As a result, concerns about Japan’s defense build-up persisted in Australia at least until the late 1980s. Nonetheless, when the Cold War ended, Australia actively sought to strengthen its security relationship with Japan and even encouraged Japan’s more active role in regional security. In reviewing subsequent developments, several success factors can be noted.

First, the two countries have gradually and comprehensively developed their security cooperation. With the beginning of defense exchanges in the early 1990s, Australia and Japan have since deepened cooperation, mainly in the areas of peacekeeping, counter-terrorism, counter-disaster and nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. When the China threat became more prominent starting in the late 2000s, their cooperation expanded to traditional military cooperation. At the same time, cooperation has deepened in areas such as capacity-building support for developing countries, infrastructure development, and economic security.

It is precisely this comprehensiveness that has ensured the continuity of Australia-Japan cooperation. For example, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) Government, which replaced the LDP government in 2009, sought a foreign policy with more independence from the United States. The DPJ government suspended the refueling mission for the U.S.-led operation by the Self Defense Forces’ ships in the Indian Ocean. At the same time, the DPJ Government was committed to strengthening international contributions and valued the SDF’s participation in peacekeeping operations and its contribution to humanitarian relief operations.

As a result, there were no objections to the conclusion of the Acquisition of the Cross Service Agreement (ACSA) with Australia, which strengthened cooperation in PKOs and humanitarian relief operations, in May 2010. Australia’s support for the SDF in its deployment to South Sudan PKO in 2013 was also welcomed by the DPJ government. The DPJ and the Australia’s Labor government also promoted initiatives for nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation, represented by the International Commission on Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament (ICNND). It was this “liberal” dimension to Australia-Japan security cooperation that has enabled the bilateral relationship to continue to develop.

Second, the two countries have consistently institutionalized their strategic partnership. In 2002, Japan, Australia and the United States launched an unofficial trilateral meeting of foreign vice ministers. It became later institutionalized as Trilateral Strategic Dialogue or TSD. TSD was upgraded to the ministerial level in March 2006. After the announcement of the Joint Declaration for Security Cooperation in March 2007, the first Foreign and Defense Ministerial Consultations or 2 plus 2 meeting was held in June of that year. Japan, Australia and the United States also launched the Security and Defense Cooperation Forum (SDCF) led by the defense authorities of the three countries in April 2007. SDCF established working groups for each agenda, such as disaster relief, missile defense, counter-piracy, bilateral exercises and non-proliferation, and interoperability and information sharing. Both TSD and SDCF continued during the DPJ-Labor period, ensuring continuity of practical cooperation between two countries.

Of course, institutionalization itself does not necessarily guarantee the continuity of security cooperation. The United States, Japan and South Korea have had several institutionalized frameworks such as the Vice Foreign Minister Meeting or Defense Working-Team Talks, known as DTT. Despite those frameworks, security cooperation between Japan and South Korea has often been suspended due to controversies over history and domestic politics factors in each of the two countries. After all, it is political will, rather than institutionalization itself, that ensures strong and sustainable relationship.

In this sense, the third and more important factor for success will be creating a shared vision of the international order for Japan and South Korea. Since the end of the Cold War, Australia and Japan have largely shared a consensus on maintaining and strengthening the liberal international order, supported by the strong U.S. military presence. In South Korea, by contrast, differences existed from regime to regime.

Both the Kim Dae-jung and Lee Myung-bak administrations emphasized maintaining the liberal order and expanding South Korea's role in global security. In contrast, the Roh Moo-hyun, Park Geun-hye and Moon Jae-in administrations focused more on peace and stability in Northeast Asia, particularly in managing inter-Korean relations, than on building a liberal international order. The popularity of the so-called “G2” idea, in which both the US and China share power and jointly lead the international order, was high in South Korea compared to that in Japan and Australia.

It is therefore welcome that the Yoon administration has announced its “Indo-Pacific Strategy” and clarified South Korea’s stance towards maintaining and strengthening a free and open international order based on the rule of law. With Japan’s vision for Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP), the two countries have now shared common goals in the Indo-Pacific region. This expanded the scope of bilateral and trilateral cooperation including the United States, which had been mostly limited to the Korean peninsula, to broader regional order-building in Indo-Pacific.

Both Japan and South Korea should continue to maintain and improve their comprehensive security cooperation and try to institutionalize such cooperation as much as possible. They should also make efforts to win bipartisan support for the FOIP and the “Indo-Pacific Strategy.” If this is possible, security cooperation between Japan and South Korea will become a built-in part of their diplomacy as an incidental element of such a strategy.

Tomohiko Satake is an associate professor at the School of International Politics, Economics and Communication (SIPEC) at Aoyama Gakuin University. Previously he was a senior research fellow at the National Institute for Defense Studies (NIDS) located in Tokyo. He specializes in international relations, Asia-Pacific security, and Japanese and Australian security policies. Between 2013 and 2014, he worked for the International Policy Division of the Defense Policy Bureau of the Japan Ministry of Defense as a deputy director for international security. He earned B.A. and M.A. from Keio University, and PhD in international relations from the Australian National University. His recent publication includes: “‘Kyori no Sensei’ wo Koete: Reisengo no Nichigo Anzenhosyo Kyoryoku” [Beyond ‘Tyranny of Distance’: Japan-Australia Security Cooperation after the Cold War] (Keiso Publishers, 2022).