- #Economy & Trade

- #Japan

- #South Korea

- #Technology & Cybersecurity

- #US Foreign Policy

► The Camp David summit on August 18, 2023, marked a new era of trilateral partnership between the US, Japan, and South Korea, expanding beyond security concerns to include economic security and technology cooperation.

► The trilateral partnership is driven by broader shifts such as US-China competition and vulnerabilities in global supply chains, leading to commitments in areas like supply chain resilience, semiconductor collaboration, and strategic economic alignment.

► The future of the partnership will depend on continued political will and leadership, especially amid upcoming changes in Japanese and US leadership and the 2027 South Korean presidential transition.

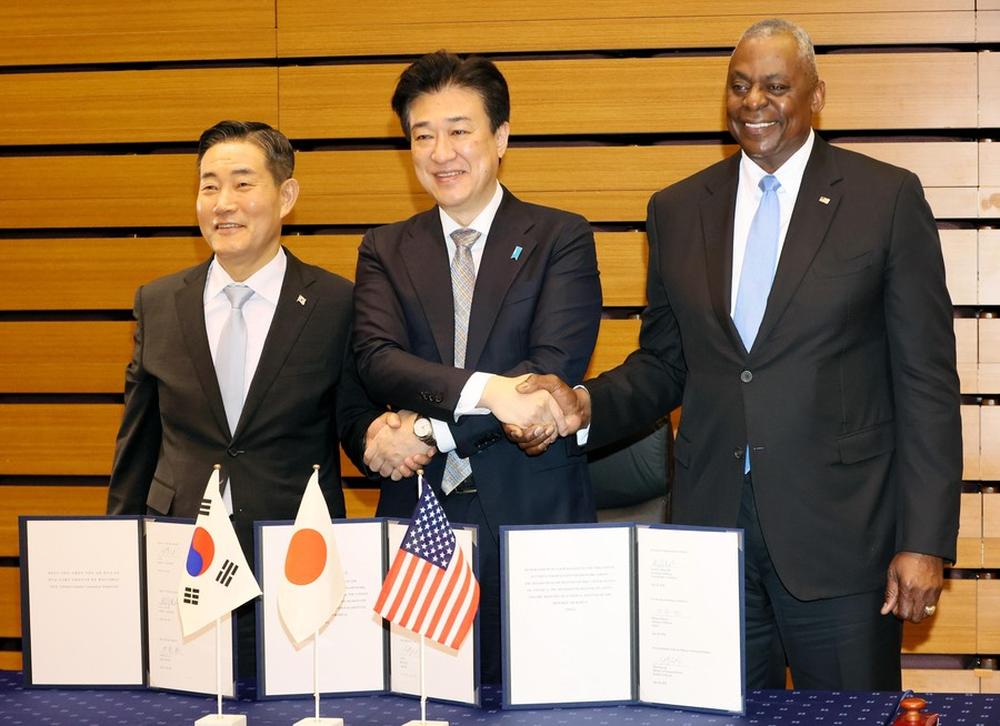

On 18 August 2023, leaders from the US, Japan, and South Korea met at Camp David to ‘inaugurate a new era of trilateral partnership’. Yet this is envisioned to do more than just address shared security interests like deterring North Korea, or even align the two most important US alliances in the region. As the joint statement that followed the summit stated, the three nations also committed to cooperate in the ‘economic security and technology spheres, leveraging the unique capabilities that each of our countries brings to bear’.

Here is further evidence of how rapidly economic security has become a critical component of national security. Two major transformations presaged this shift: first, against the backdrop of intensifying US-China competition, Washington and Beijing have ‘weaponized’ their economies to achieve geopolitical objectives; and second, the pandemic exposed how dependance on globalized supply chains creates economic vulnerabilities. From ‘re-shoring’ to ‘de-risking’, much of the economic security rhetoric reflects a realization that in a crisis the value chains constructed in an era of trade liberalization are ripe for geopolitical manipulation. In this context, the economic security dimension to the US-Japan-South Korea trilateral partnership should be given greater attention.

At Camp David, the three nations committed to cooperate in several key areas. Supply chain resilience is at the heart of the partnership, such as efforts to diversify the sources of critical minerals and components, and the establishment of a ‘joint early warning system’ to detect and mitigate disruptions. So is technology cooperation. This includes the formalization of a ‘semiconductor alliance’ to stabilize chip supplies, enhance R&D, and build up manufacturing capacity, in addition to commitments to work together on hydrogen technology, nuclear energy, and advanced batteries. Another aspect is the formation of a ‘strategic economic alignment against coercion’, facilitating discussions on export controls and investment screening, as well as enabling a collective response to arbitrary trade restrictions or technology theft.

These commitments built on several prior discussions, beginning in 2021. But it is important to point out the role of leadership and political will in bridging the gap between Tokyo and Seoul. It is unlikely that President Biden would have been able to advance such a trilateral partnership without Prime Minister Kishida and President Yoon’s exemplary efforts toward repairing bilateral relations. In fact, as Kishida left office on 1 October 2024 with very low domestic approval ratings, many observers noted that his greatest achievements may have been on the international stage—especially strengthening Japan’s ties with South Korea.

This raises the question of whether new Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba will continue to follow the course set out by Kishida. Compared to Sanae Takaichi, his run-off opponent for leader of the ruling LDP, Ishiba was considered to be more favorable to sustaining the Japan-South Korea rapprochement. Furthermore, one of his foreign policy ambitions is to create an ‘Asian NATO’ out of the US-led ‘hub-and-spokes’ security architecture in the Indo-Pacific. Although this larger idea may prove infeasible, in making his case Ishiba praised Kishida’s efforts to bring the US-Japan and US-South Korea alliances toward a ‘real trilateral alliance’. If Ishiba truly wants to move in the direction of an ‘Asian NATO’, the first logical step would be to cement the nascent US-Japan-South Korea partnership.

Similarly, in terms of economic security, the Ishiba administration is not expected to deviate from the path forged by Kishida, as Japan’s 2022 Economic Security Promotion Act has institutionalized many of the domestic components to trilateral cooperation in this area. The appointment of Minoru Kiuchi, a former diplomat, as Economic Security Minister also signals that Japan will continue to work with likeminded partners to secure supply chains for semiconductors and critical minerals.

A more serious challenge on the horizon could come from the US election. Both former President Trump and Vice President Harris have focused their campaigns on domestic issues and their respective positions regarding the US-Japan-South Korea trilateral are unclear. At this point, Harris is expected to continue many of Biden’s Indo-Pacific policies, although she will almost certainly bring in her own national security team.

Trump, however, seems on the surface to present a greater threat to the trilateral partnership. In his first term he clearly preferred to engage in bilateral diplomacy, and publicly called on Japan and South Korea to increase defense spending and shoulder more of the financial burden for their alliances. But there are signs a second Trump term would not simply be a repeat of the first. As a Washington newcomer, Trump did not have the team of trusted foreign policy advisors he does now, such as former National Security Advisor Robert O’Brien, who is anticipated to have a senior role in a second Trump administration. O’Brien has repeatedly affirmed the value of the US-Japan and US-South Korea alliances, as well as the Quad (which he recently suggested should admit South Korea), as a strategic advantage in US competition with China.

With respect to economic security, it is noteworthy that some of the only issues that receive bipartisan support in Washington are confronting China’s economic coercion, rebuilding American manufacturing, and securing supply chains. Both the Trump and Biden administrations have attempted to limit China’s access to advanced technologies on national security grounds, and both engaged in the strategic use of trade and industrial policies. Nevertheless, there were some differences in their use of these instruments. Unless Trump is more strategic with tariffs than his rhetoric suggests—focusing them on China rather than US allies—the economic security dimension of the trilateral could falter. For instance, in the last five years, the post-pandemic slowdown in the Chinese economy and cutthroat domestic competition caused the share of Japanese and South Korean exports going to China to decrease, while at the same time their share of exports going to the US increased. Trump may see this as a US weakness rather than a complimentary relationship among allies that showcases the robustness of the US economy.

If the next US president can sustain and enhance the trilateral partnership, its real test may come in 2027 when Yoon is replaced. From a Japanese standpoint, a return to the policies of the Moon administration would strengthen the more hawkish elements in the LDP, which might combine to produce a downward spiral in Japan-South Korea relations. Neither Harris nor Trump would be able to shift domestic sentiments without the corresponding political will in Tokyo and Seoul.

Hopefully, Kishida and Yoon have already accomplished the most difficult task. The macro factors that incentivized further trilateral cooperation—especially on economic security—will not go away anytime soon. China is continuing to move up the value chain in semiconductors, batteries, and automobiles, creating greater competition and dependencies. Trade, technology, manufacturing, mining, and supply chains are now accepted as vital to national security. So long as future leaders in the US, Japan, and South Korea believe that aligning the most technologically advanced nations will enhance their individual competitiveness, the trilateral will continue to be a pillar of their economic security policies. But as always, it will be a question of leadership.

—

Andrew Capistrano is a Visiting Research Fellow in the Economic Security Group at the Institute of Geoeconomics, Tokyo. A diplomatic historian by training, he holds a BA from the University of California, Berkeley, and a PhD from the London School of Economics.