- #Security & Defense

- Three out of the four IP4 partners (South Korea,

Japan, Australia) declined the invitation to attend on short notice.

- Efforts to move the IP4 partnership from dialogue to

action in operational, defence industrial, technology cooperation, and maritime

security risks faltering, thereby weakening its intended deterrence,

particularly to prevent a ‘Taiwan contingency’.

- President Lee's absence due to urgent domestic

matters could be beneficial for South Korean politics.

Volatility and change are the defining characteristics

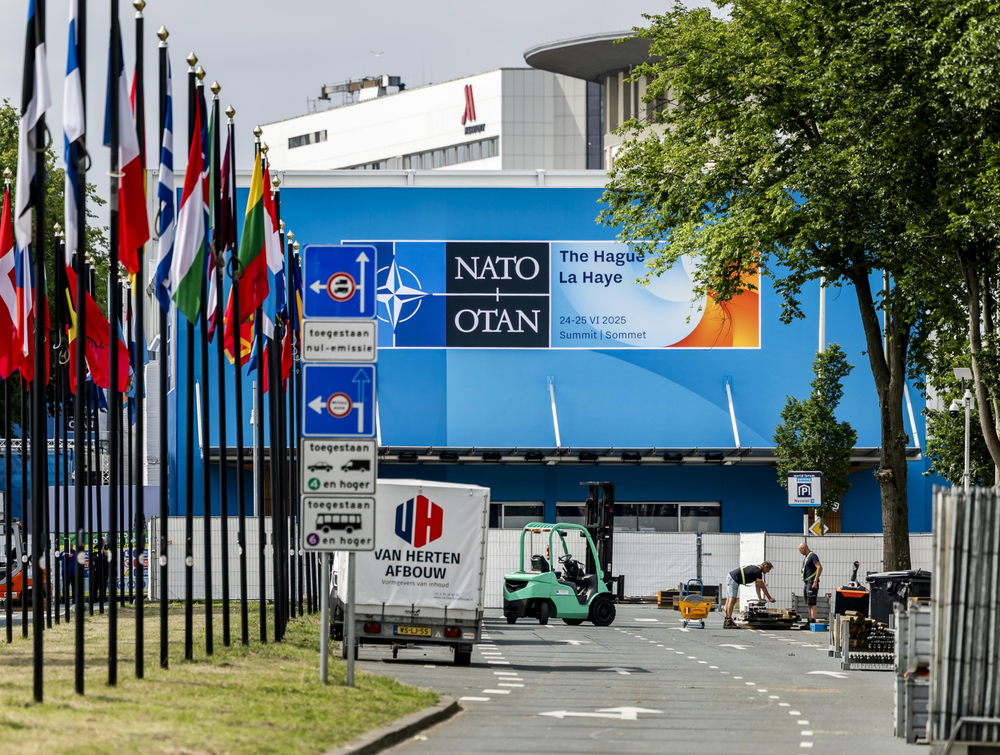

of contemporary politics. Rather than focusing on the outcomes of President

Lee's participation in the NATO Summit in The Hague, this analysis centres on

the implications of non-participation.

Three out of the four IP4 partners (South Korea,

Japan, Australia) declined the invitation to attend on short notice. Only the

New Zealand Prime Minister proceeded with the visit, as it was part of a larger

trip that included Beijing, Brussels and the Flanders Fields. This

non-attendance deviates from the tradition established at the 2022 Madrid

Summit.

First, there is a valid logistical reason: having just

returned from the G7 Summit in Canada, another long-distance flight would keep

key decision-makers out of domestic politics at a crucial time. While this fact

was known from the outset, it weighs in stronger for President Lee Jae-myung,

who is only a few weeks into his presidency.

Second, expectations have changed. Unlike previous

summits, The Hague summit focused more on ‘internal’ matters rather than

programmatic issues. NATO members struggled in advance to agree on a 5% of GDP

defence spending increase by 2035, dividing it into 3.5% for defence and 1.5%

for related infrastructure to reach a compromise. President Trump, known for

his lack of enthusiasm for NATO, made organisers arrange a lavish dinner, an

overnight stay in the Dutch royal palace, and only one brief working session to

keep him engaged.

Avoiding a direct discussion of Article 5, NATO's core

deterrence principle, to prevent Trump from questioning it, was not only

uninspiring but spread doubt about the Alliance’s cohesion, although finally

confirmed as “ironclad commitment”.

Third, all IP4 leaders were disappointed that at the

G7 Summit the planned meetings with President Trump did not materialise because

of his premature and abrupt return to Washington, allegedly because of the

Israel-Iran war. Another disappointment would have conveyed the message of US

disinterest and gone down badly with the respective publics and therefore had

to be avoided. Kiwi PM Christopher Luxon suffered this fate; despite attending

the NATO summit, he was not granted an audience. This aspect was especially

important for President Lee as he is looking for the opportunity for his first

personal encounter with the US president to discuss economics, security and the

alliance.

A missed opportunity or a smart move?

The short Summit statement did not refer to the

Indo-Pacific, Asia, China, North Korea and Russia, in stark contrast to the

2024 Washington Declaration (“The Indo-Pacific is important for NATO, given

that developments in that region directly affect Euro-Atlantic security.”).

This is also contrary to the preceding G7 statement which contains a whole

paragraph on the Indo-Pacific and China. While this can be explained away by

the above-described specific nature of this summit, there remains a stale

taste. NATO’s outreach to the Indo Pacific and a considerable public diplomacy

effort to present itself in the region aimed at conveying the message that the

Trans-Pacific and the Trans-Atlantic theatres are closely linked as there is

only one security; China had been singled out as being of special concern.

This narrative certainly damaged trust in the US as a

reliable alliance partner and main security provider, not only in Europe but

also in Asia. This spurred a discussion in the IP4 countries: South

Korea’s public sees value in going nuclear; Japan as well as New Zealand are

planning a conventional upgrade; Australia worries about an announced AUKUS

review impacting its nuclear submarine project, which came at a significant

diplomatic cost after shifting away from France.

If the non-participation aimed to avoid discussing the

increase in defence budgets, it will not stop the topic from being imposed by

the US. South Korea had tried at the closing days of the Biden

Administration in October 2024 a pre-emptive strike in settling with the US for

on a new five-year deal, consisting of an increase of 8.3% in the first year

(reaching $1.125 billion) with further annual increases at maximum of 5%. The

likelihood that President Trump returns to the Korean “money machine” is high.

In addition, South Korea has already built Camp Humphrey, the largest US

overseas military base, at the considerable cost of US$11 billion. The other

three IP4 partners will not be spared either.

Efforts to move the IP4 partnership from dialogue to

action in operational, defence industrial, technology cooperation, and maritime

security risks faltering, thereby weakening its intended deterrence,

particularly to prevent a ‘Taiwan contingency’.

This is in stark contrast to the statement on the

official NATO website: ”In today’s complex security environment, relations with

like-minded partners are increasingly important to address cross-cutting

security issues and global challenges. The Indo-Pacific is important for the

Alliance, given that developments in that region can directly affect

Euro-Atlantic security.”

A lower-level meeting of officials from the IP4 with

SG Rutte confirming in a statement everything one had expected the leaders to

confirm, is an exercise of damage control but cannot conceal the return of the

Transatlantic focus, not least as the US regards the Transpacific as its main

domain.

Domestic politics in South Korea

President Lee's absence due to urgent domestic matters

could be beneficial for South Korean politics. Already candidate Lee Jae-myung

had hinted in May that he might not participate in the NATO summit and was

critical of the foreign policy of his by now disgraced predecessor Yoon

Suk-yeol who had attended three NATO summits.

Thus, he appeals to parts of his former Democratic

Party that are wary of closer US ties and want to avoid upsetting China and

Russia. At the same time in counterbalancing the presidential absence and

making good use of the damage-control exercise mentioned, the National Security

Advisor Wi Sung-lac, acting as special presidential envoy, established with

NATO Secretary General Rutte a working-level consultative body on defence

industry cooperation to discuss specific measures to enhance cooperation in the

sector. Considering South Korea’s multibillion dollar arms sales to backfill

Ukraine, this move appears to be an early expression of President Lee’s

‘pragmatic foreign policy’, based on South Korea’s national interest.

Finally, President Lee as the host of the 2025 APEC

Sumit at the end of October in Gyeongju, has a strong interest to attract

leaders. This includes Chinese President Xi for a long-awaited summit. The APEC

summit also serves as an alternative opportunity for a meeting with President

Trump to discuss trade and security issues, if neither an earlier bilateral

meeting nor one in the margins of the UN General Assembly are feasible. This

assumes that Trump's interest in trade deals may motivate him to attend the

APEC Summit.

Dr. Michael Reiterer (michael.reiterer@vub.be ) Professor for International Security, Diplomacy and Strategy, Brussels School of Governance; Adjunct Professor for International Politics, University of Innsbruck (habilitation 2005, PhD equivalent), Webster University/Vienna, LUISS/Rome, Danube University/Krems; Guest professorships at Ritsumeikan University/Kyoto, Kobe and Keio University/Tokyo. Associate Fellow – Global Fellowship Initiative, Geneva Centre for Security Policy (GCSP), Senior Advisor at Centre for Asia Pacific Strategy (CAPS), Washington DC, Austria Institute for Europa and Security Policy (AIES) Vienna, and Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW). Ambassador of the European Union to the Republic of Korea (2017-2020), Switzerland and the Principality of Liechtenstein (2007-2011) rtd. Previously Minister, Deputy Head of EU-Delegation to Japan (2002-2006); ASEM Counsellor (1998-2002); Minister-Counsellor, Austrian Mission to the European Union (1997-98); Counsellor, Austrian Mission to the GATT (1990-92); Austrian Deputy Trade Commissioner to Japan (1985-88) and Western Africa (1982-85). Panellist at WTO dispute settlement; Co-chair Trade of Joint Group of Trade and Environment Experts, OECD. Honorary citizen of Seoul (2020); Order of Merit in Silver with Star, Government of the Republic of Austria (2018).