- #Energy & Climate

- #South Korea

- #Technology & Cybersecurity

Key Takeaways:

- Operating large data centers, training massive AI models, and running advanced semiconductor fabs all require enormous and stable supplies of electricity.

- Nuclear power stands out as the most realistic solution to Korea’s twin challenges of energy security and carbon neutrality.

- By integrating robust energy infrastructure, world-class semiconductor capabilities, forward-looking policy, and active international engagement, Korea can transform itself into a true AI powerhouse.

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as one of the most revolutionary forces of the 21st century, fundamentally reshaping the global landscape of industry, trade, security, and international relations. For South Korea, a nation whose economic miracle was built on manufacturing excellence and technological advancement, the changes from AI present both an unprecedented opportunity and a formidable challenge. The future of Korea’s national competitiveness will be determined not only by its ability to develop and deploy cutting-edge AI technologies but also by its capacity to secure the vast energy resources and international partnerships required to sustain an advanced AI ecosystem.

The global race for AI supremacy is not simply a matter of technological rivalry; it is a battle that will set the course of economic and geopolitical dominance for generations to come. The United States and China, the two leading AI powers, are investing hundreds of billions of dollars in research, infrastructure, and human resources, seeking to dominate not only the commercial applications of AI but also its strategic and military dimensions. In this context, South Korea’s ambitions to become an AI powerhouse must be understood as part of a broader effort to assert its sovereignty and influence in a rapidly shifting international order. This will require not only industrial leadership but also agile diplomacy, as AI norms, standards, and supply chains become significant domains of geopolitical negotiation.

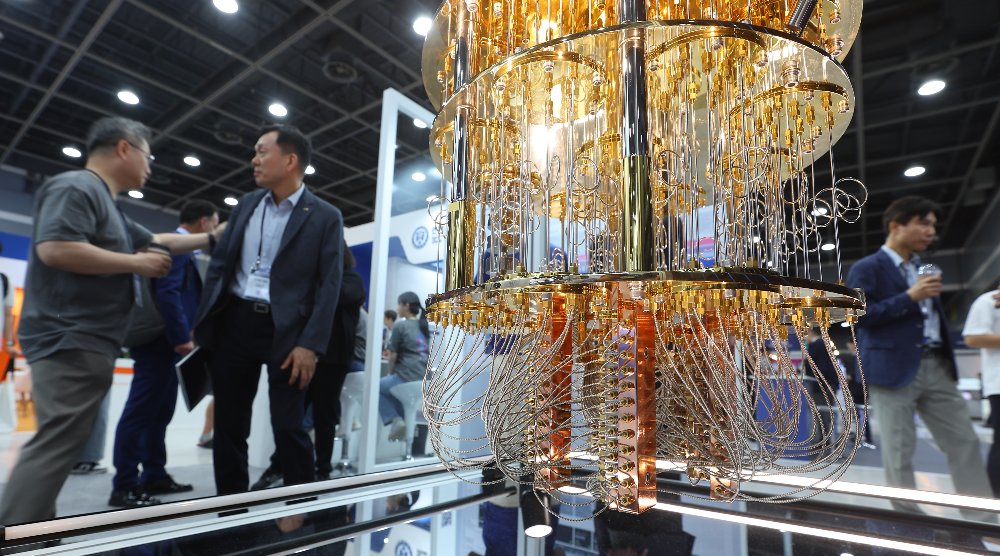

At the heart of this transformation lies the semiconductor industry, the “brains” of the digital economy and the essential hardware that powers AI systems. Korea has long been a global leader in memory semiconductors, with companies like Samsung Electronics and SK Hynix dominating global markets. However, as AI applications grow more sophisticated, the demand is shifting. While market demand is moving toward system semiconductors and AI-specialized chips, Korea’s global competitiveness in these areas remains weaker than that of the United States, Taiwan, and China. Recognizing this, the Korean government has launched the ambitious “K-Semiconductor Strategy,” pledging over 600 trillion KRW in public and private investment by 2030 to build the world’s largest semiconductor supply chain. This includes not only expanding production capacity but also fostering innovation in chip design, materials, fabrication, and advanced manufacturing technologies. The initiative also emphasizes supply chain security, ensuring that critical components are sourced from stable and politically reliable partners – a lesson underscored by recent geopolitical disruptions.

Yet, the success of Korea’s AI and semiconductor ambitions depends on a pivotal factor often overlooked by the public: energy. Operating large data centers, training massive AI models, and running advanced semiconductor fabs all require enormous and stable supplies of electricity. According to the International Energy Agency, global data center power consumption is expected to more than double by 2026, driven largely by the exponential growth of AI workloads. In the United States, some analysts predict that AI-related electricity demand could increase eightyfold within a decade. Korea, with its world-class power grid and relatively low electricity costs, enjoys a comparative advantage in attracting high-tech industries. However, sustaining this advantage in the face of surging demand and climate change commitments will require a fundamental transformation of the national energy system.

Nuclear power stands out as the most realistic solution to Korea’s twin challenges of energy security and carbon neutrality. Unlike fossil fuels, nuclear energy provides stable, 24-hour baseload power with minimal carbon emissions. The development of small modular reactors (SMRs) offers additional flexibility, allowing for the deployment of distributed power sources tailored to the needs of specific industrial clusters, such as AI data centers and semiconductor clusters. By expanding its nuclear capacity and integrating smart grid technologies, Korea can ensure that its digital and industrial infrastructure remains resilient, efficient, and environmentally sustainable.

However, the energy question is not merely a technical or economic issue; it is deeply entangled with international politics and security. The global supply chains for nuclear technology, uranium fuel, and advanced reactor components are subject to geopolitical risks, such as export controls, international sanctions, and competition among global powers. Korea must navigate its alliances with the United States and its economic ties with China, both of which are seeking to shape the rules and standards of the emerging AI and energy order. The recent disruptions in semiconductor supply chains, triggered by US-China rivalry and the COVID-19 pandemic, have underscored the vulnerability of globalized production networks. In response, Korea is pursuing greater self-reliance in critical materials and technologies, while also strengthening cooperation with trusted partners in the United States, Europe, and Southeast Asia.

Beyond technology and energy, the rise of AI raises profound questions about governance, ethics, and global standards. As AI systems become more pervasive and powerful, concerns about privacy, security, bias, and accountability are becoming major issues. Korea is preparing to implement its “AI Basic Act” in 2026, introducing differentiated regulations for high-risk AI applications while preserving space for innovation. Yet, national legislation alone is insufficient to address the cross-border challenges arising from AI. International cooperation is essential to establish common norms for data protection, algorithmic transparency, and the responsible use of AI in areas such as surveillance, autonomous weapons, and critical infrastructure. Korea, as a technologically advanced democracy, has a unique opportunity to contribute to the shaping of global AI governance, working through multilateral forums such as the OECD, G20, and the United Nations.

The global competition for AI human resources is fierce, with leading countries offering generous incentives to attract top researchers, engineers, and entrepreneurs. Korea must invest heavily in education and training, from primary schools to universities, to cultivate a new generation of AI experts. International collaborations, joint research projects, and expert exchange programs with leading institutions abroad can help Korea build a vibrant and diverse AI ecosystem. At the same time, fostering a culture of ethical innovation and social responsibility will be vital to ensure that technological progress serves the broader public good. To achieve this, ethics, law, and the humanities must be integrated into AI courses, equipping engineers with an understanding of how their creations shape society.

Ultimately, the energy-based AI ecosystem is not simply a matter of industrial policy or technological competition. It is a comprehensive national project that will shape Korea’s economic prosperity, social stability, and international standing in the decades ahead. By integrating robust energy infrastructure, world-class semiconductor capabilities, forward-looking policy, and active international engagement, Korea can transform itself into a true AI powerhouse. The challenges are formidable, ranging from technological and energy transitions to geopolitical rivalries and ethical dilemmas. But with decisive action, forward-looking strategy, and a commitment to global cooperation, Korea can not only survive but thrive in the new era of AI-driven global competition—securing its place as a leader in both industry and international relations.

Jiyoung Park is Chief Director at the Research Institute for Economy and Society. Her main research area is science, technology, and security policy. Her current interests include policy and management issues related to nuclear technology, security challenges posed by emerging technologies, and evidence-based science and technology policies. Park holds a Ph.D. in nuclear engineering and radiological sciences.