Key Takeaways:

- ICE’s raid on Hyundai has raised alarms among major Asian investors in the U.S., signaling that even aligned partners are not immune to political or regulatory shocks.

- Taiwan—deeply invested in U.S. semiconductor manufacturing through TSMC—faces rising risks amid Trump-era uncertainties on labor, tariffs, and industrial policy.

- To safeguard its strategic semiconductor edge, Taipei must diversify investments, institutionalize economic-security dialogue with Washington, and build resilient linkages with other regional allies.

Following the recent immigration raid conducted by the

US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) on the Hyundai Motor Group’s

offices in September, over alleged labour and immigration violations in its

supply chain, concerns have grown among other industrial partners about how and

to what extent the incident might affect the broader investment and

geopolitical climate. Major investors from US allies such as Taiwan and Japan

are now bracing for potential spillover effects as Washington signals a tougher

stance on border and foreign worker enforcement.

If Hyundai

can face such treatment despite its alignment with US industrial and strategic

goals, what might await Taiwan’s Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company

(TSMC) or Japan’s semiconductor ventures in the States? While an immigration

inspection might appear to be a routine legal matter, for Taiwan, whose

semiconductor champion has invested tens of billions of dollars into its

Arizona fabs, the stakes could not be higher. Taipei should consider

recalibrating its semiconductor investment strategy by diversifying its outward

investment, institutionalising economic-security dialogue, coordinating

regionally with other investor allies, and strengthening domestic capacity to

mitigate any potential backlash from the US political uncertainty under the

second Trump administration on its semiconductor investment.

Taiwan’s

Semiconductor Dilemma in the US

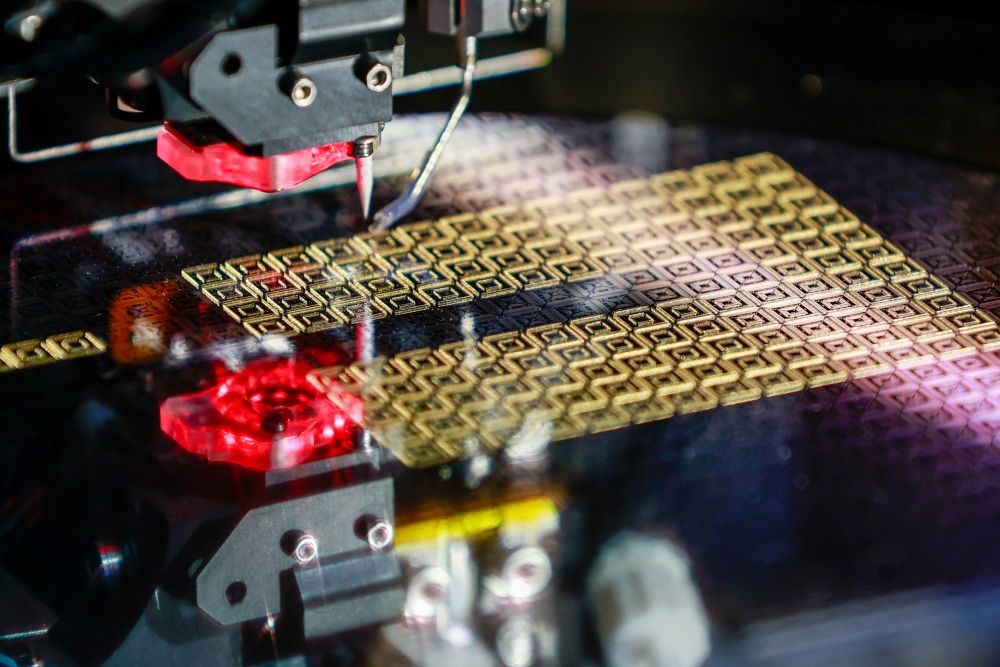

The

enactment of the CHIPS and Science Act in 2022 under the Biden administration

marked a new phase in the US de-risking industrial strategy aimed at attracting

investment from allied partners and diversifying semiconductor supply chains

away from China. The U$278.2 billion act seeks to bolster U.S. manufacturing

capacity for advanced, leading-edge semiconductors currently produced abroad, increase

the supply of mature-node chips, promote research and development within the

semiconductor industry, and create thousands of new domestic jobs[1].

The Act

appeals to giant manufacturing companies such as TSMC and to the Taiwanese

government in deepening economic alignment with the US, given the role

semiconductors have played as a security shield deterring potential aggression

or occupation by Beijing. However, significant challenges remain in sustaining

long-term manufacturing investments. The Arizona fabs, for instance, have

encountered issues, such as workforce safety concerns, a shortage of skilled

labour, differences in work culture between Taiwanese and American employees,

and high operating costs[2].

This

condition has been further amplified by potential uncertainties created by

Trump 2.0. administration, especially on the imposition of high tariffs on

imported chips, as well as possible restrictions on foreign labour employment

stemming from the US’s new immigration policies under the ICE regime. A dilemma

arises for policymakers and semiconductor stakeholders in Taipei, as

withdrawing investments from the US is not a feasible option due to Taiwan’s

geopolitical tension vis-à-vis China, which makes continued economic and

political support from Washington essential. On the other hand, remaining too

deeply invested in the US market requires strategic measures to avoid putting

all of Taiwan’s eggs in one basket, especially amid the resurgence of an ‘America

First’ policy approach.

Diversifying

Taiwan’s Semiconductors Outward Investment

To strengthen

sustainability in semiconductor manufacturing and enhance supply chain

resilience, Taiwan should diversify its overseas investments beyond the US. TSMC

has already expanded production in Japan and Germany, while United

Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) continues to grow its manufacturing and

R&D operations in Singapore. By 2027, Vanguard International Semiconductor

Corporation, a TSMC subsidiary collaborating with Dutch Chipmaker NXP

Semiconductors, is expecting to produce its first batch of chips at its US$7.8

billion wafer fabrication plant in Singapore[3].

Among

several options in European and East Asian countries, Southeast Asia emerges as

a feasible and strategic destination for such diversification for several

reasons. First, the region offers cost-competitive manufacturing environments,

established electronics ecosystems, and increasingly supportive industrial

policies in countries such as Singapore, Malaysia, and Vietnam. Second, their

geographical proximities to Taiwan further enhance logistical efficiency and

access to skilled engineering talent. Third, in the event of a cross-strait

war, the US and its allies, such as Japan and those in Western European

countries, would likely be preoccupied with defending Taiwan. In contrast, many

Southeast Asian nations may adopt a neutral stance, reducing the likelihood of

a complete halt in chip production and thereby sustaining supply chain

resilience[4].

Nonetheless,

challenges such as political instability, poor infrastructure, and a limited

talent pool could constrain efforts to scale up advanced semiconductor

technology. Taiwan, thus, should carefully assess whether the disadvantages of

expanding manufacturing in Southeast Asia may outweigh the potential benefits.

Institutionalising

Economic-Security Dialogues and Coordinating Regionally

One way

Taipei can ensure more predictable investment conditions is by advocating for

the establishment of a formal US-Taiwan Economic Security Dialogue. This

framework could include dispute-resolution mechanisms and clear rules governing

subsidy compliance. Although high-level official dialogues are unlikely due to

the One China policy and the absence of formal diplomatic relations,

institutions such as the American Institute in Taiwan (AIT) and the Taipei

Economic and Cultural Representative Office (TECRO) in Washington, DC, could

act as effective intermediaries to facilitate such exchanges. In addition, Track

1.5 and Track 2 dialogues on economic security should also be pursued to deepen

mutual understanding between Taipei and Washington.

Another channel

that Taiwan can utilise is regional coordination with other US allied

industrial partners, such as South Korea and Japan. A trilateral investment

forum could be organised under a regional economic framework, where Taiwan is a

member, including the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC). Such an

investor alliance could facilitate regular consultations on regulatory trends

and labour compliance issues affecting their investments. This minilateral

economic bloc would help build solidarity and strengthen its collective

bargaining position in relation to the US investment climate.

Strengthening

Semiconductor Domestic Capacity

While

diversifying its semiconductor investment abroad, Taiwan should also strengthen

its domestic production capacity by investing in workforce training, R&D

incentives, and next-generation technologies such as advanced packaging and

photonics. By focusing on its domestic capacity, Taiwan can also sustain its

talent pipeline for both domestic and overseas chip industries, particularly by

recruiting young professionals from Southeast Asian countries who have been

educated in Taiwan. TSMC, for example, has been actively recruiting talented

students from Southeast Asia and India to gain working experience through

internships.

Another

domestic aspect that requires attention is providing subsidies and incentives

to encourage a sustainable domestic supply chain. While the introduction of the

Industrial Innovation Statute in 2023 opened a new window of opportunity to

boost domestic capacity by offering tax incentives and funding to drive

technology advancement, the act should be more thorough in supporting domestic

and medium-scale firms[5]. Such efforts would help

sustain Taiwan’s position as a global leader in semiconductor technology,

thereby enhancing its geopolitical and economic leverage amid rising pressure

from China.

[1] Emily Benson, Japhet Quitzon, and William A. Reincsh, Securing

Semiconductor Supply Chains in the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for

Prosperity: Squaring the Circle on Deeper Cooperation, CSIS, May 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/securing-semiconductor-supply-chains-indo-pacific-economic-framework-prosperity

[2] Michael Sainato, ‘They would not listen to us’: inside Arizona’s

troubled chip plant, The Guardian, 28 August 2023,https://www.theguardian.com/business/2023/aug/28/phoenix-microchip-plant-biden-union-tsmc

[3] Elyssa Lopez, TSMC subsidiary to co-build $7.8b Singapore chip

wafer plant, Tech in Asia, 5 June 2024, https://www.techinasia.com/nxp-tsmcbacked-vanguard-plan-78-billion-chip-plant-construction-singapore

[4] Chin Shueh, How Taiwan-ASEAN Semiconductor Cooperation Can Bolster

Taipei’s National Security, The Diplomat, 23 December 2023, https://thediplomat.com/2023/12/how-taiwan-asean-semiconductor-cooperation-can-bolster-taipeis-national-security/

[5] Monica Chen, Rodney Chan, Taiwan ‘Chips Act’ to benefit only a few

companies, Digitimes Asia, 29 March 2023, https://www.digitimes.com/news/a20230328PD213/chips-act-ic-design-ic-manufacturing-taiwan-tsmc.html

Ratih Kabinawa is an Adjunct Research Fellow at the University of Western Australia and a Research Fellow at Forum Sinologi Indonesia. She earned her doctoral degree in International Relations and Asian Studies from the University of Western Australia. Her research interests include Taiwan’s foreign policy, Taiwan-Southeast Asia relations, geopolitics, labour migration, and the diplomacy of non-state actors. She was a Taiwan MOFA Visiting Research Fellow and Taiwan Foundation for Democracy Postdoctoral Research Fellow.