- #Economy & Trade

- #Technology & Cybersecurity

- #US Foreign Policy

- #US-ROK Alliance

► The strong alignment between Seoul and Washington on their North Korea policy could provide an opportunity for the Yoon administration to be in the driver’s seat—possibly with Washington’s full support. This could increase Seoul’s bargaining position and leverage vis-à-vis Pyongyang and help the inter-Korean dialogue start from a different vantage point.

► As South Korea pivots toward the United States, the Yoon administration needs a China strategy that would enable it to manage future risks in its relationship with China.

► It is crucial and necessary for Seoul and Tokyo to focus on the areas of their policy overlaps and work together to create positive momentum for their bilateral cooperation.

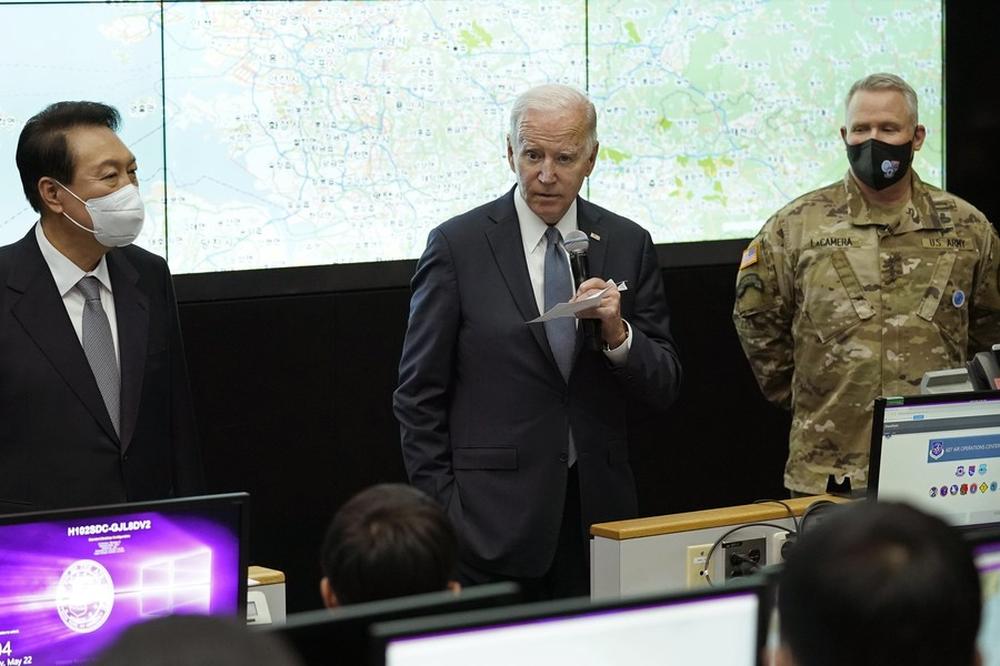

The first summit between U.S. President Joe Biden and South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol was a good start for both countries. During Biden’s three-day visit to South Korea, he built a good rapport and “genuine connection” with Yoon. The summitry also demonstrated the enduring strength of the U.S.-ROK military alliance, the two countries’ expanding economic and technology partnership, and their shared commitment to freedom, democracy, and the rules-based international order. In this briefing, I discuss the key achievements from the first Biden-Yoon summit and what’s next for South Korea going forward.

Key Outcomes from the Biden-Yoon Summit

One of the major outcomes was the clear U.S. extended deterrence commitment to South Korea delivered at the highest-level. The joint statement released after the two leaders’ summit meeting spelled out the U.S. commitment to defend South Korea, “using the full range of U.S. defense capabilities, including nuclear, conventional, and missile defense capabilities.” The inclusion of nuclear defense capabilities was significant because it was intended to assuage the growing skepticism in South Korea about the credibility of U.S. extended deterrence, especially in the wake of North Korea’s 16 missile tests this year and amid new warnings about the country’s nuclear test during Biden’s Asia trip. The Biden and Yoon administrations also agreed to resume the high-level Extended Deterrence Strategy and Consultation Group (EDSCG) and the joint U.S.-ROK military exercise to bolster their joint deterrence posture and defense capabilities in the face of North Korea’s burgeoning missile and nuclear threats.

Another notable development was the new U.S.-ROK partnership on issues of economic security. The two leaders announced a “strategic economic and technology partnership” between the United States and South Korea to establish a secure and stable supply network of essential products, such as semiconductors and batteries, and protect their countries’ critical and advanced technology. Economic security became a vital national security interest of many countries, especially after the Covid-19 pandemic disrupted the global supply chain network, and interdependence is increasingly weaponized by countries as a policy instrument to coerce others. During his joint press conference with Biden, Yoon said, “We live in an era where economy is security and security, in turn, is economy. Supply chain disruptions resulting from a change in global security order are directly linked to the lives of our people.”

Finally, the U.S. and South Korea showed their growing agreement in their Indo-Pacific strategies that was absent before. In the joint statement, South Korea expressed its support for a free and open Indo-Pacific. The country also announced its participation in the U.S. Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF). For the Yoon administration, its participation in the IPEF was largely driven by its desire to participate in the regional rule-making process, particularly in the areas of trade facilitation, supply chain resilience, decarbonization and clean energy, and tax and anti-corruption. This is also in line with the Yoon administration’s vision of South Korea as a “global pivotal state” that plays a more active regional and global role. However, China perceived the IPEF as the new U.S. regional economic strategy to exclude China and counter its economic influence in the Indo-Pacific. Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed China’s opposition to South Korea’s participation, calling it Seoul’s “decoupling” from Beijing.

What’s Next for South Korea?

The successful Biden-Yoon summit leaves several important tasks behind for South Korea. One is how to reset inter-Korean relations and discourage North Korea from its weapon testing and other destabilizing activities. This is no easy task at all, especially when Pyongyang shows no appetite for dialogue and is focused on its continuous nuclear and missile development. China is also uninterested in facilitating the denuclearization talks, and Washington is preoccupied with China and Russia. Despite this unfavorable environment, the strong alignment between Seoul and Washington on their North Korea policy could provide an opportunity for the Yoon administration to be in the driver’s seat—possibly with Washington’s full support. This could increase Seoul’s bargaining position and leverage vis-à-vis Pyongyang and help the inter-Korean dialogue start from a different vantage point.

Another important task is related to China. During their meeting, Biden and Yoon distanced themselves from sensitive issues that could provoke China, such as the U.S. THAAD deployment to South Korea and South Korea’s missile defense cooperation with the U.S. and Japan. It seems unlikely that Beijing will retaliate against Seoul for the latter’s participation in the IPEF. However, as South Korea pivots toward the United States, the Yoon administration needs a China strategy that would enable it to manage future risks in its relationship with China. The economic security dialogue channel established between South Korea’s presidential office and the White House National Security Council could be useful in this regard so that Seoul and Washington could coordinate their response if Beijing flexes its economic muscles against Seoul. Washington should also be ready to provide strong political, diplomatic, and economic support to Seoul to prevent this from becoming a source of friction in their alliance.

Finally, the Yoon administration will need to improve South Korea’s relationship with Japan. Yoon already indicated his strong interest in repairing Seoul’s fraught ties with Tokyo and sent a government delegation to Japan. The Kishida administration reciprocated this with Japanese foreign minister Yoshimasa Hayashi’s visit to South Korea to attend Yoon’s inauguration ceremony. But domestic political barriers still abound in each country to overcome their mistrust toward each other and make a meaningful step to improve their bilateral relationship. South Korea and Japan are also heading into local and upper house elections in June and July, respectively, which means it will be difficult for both countries to find a political space until this fall. Under these circumstances, it is crucial and necessary for Seoul and Tokyo to focus on the areas of their policy overlaps and work together to create positive momentum for their bilateral cooperation. Addressing their shared concern about the North Korean nuclear and missile threats appears to be the ideal starting point. Both the Yoon and Kishida administrations also share a strong commitment to freedom, democracy and the rules-based international order and the desire to build a stable supply chain network in the region, which could help bring them together and move their dialogue forward.

Ellen Kim is deputy director of the Korea Chair at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), where she is also a senior fellow. Her research focuses on U.S.-Korea relations and U.S.-China strategic competition in the Indo-Pacific. She joined the Korea Chair upon its inception in 2009 and previously served as associate director and fellow before her departure in 2015. She holds a PhD in political science and international relations from the University of Southern California, an MPP from the Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, and a BA in international relations and Japanese studies from Wellesley College.